I have a range of interests with trains that encompass genres like art, storytelling, architecture, woodworking and design, and I draw upon the resources of each to find inspiration for my approach to modeling. It’s how I work and where I find the most satisfaction in the work. The cameo project I’m pursuing embraces many of the insights I’ve learned from these non-traditional sources, especially art and design.

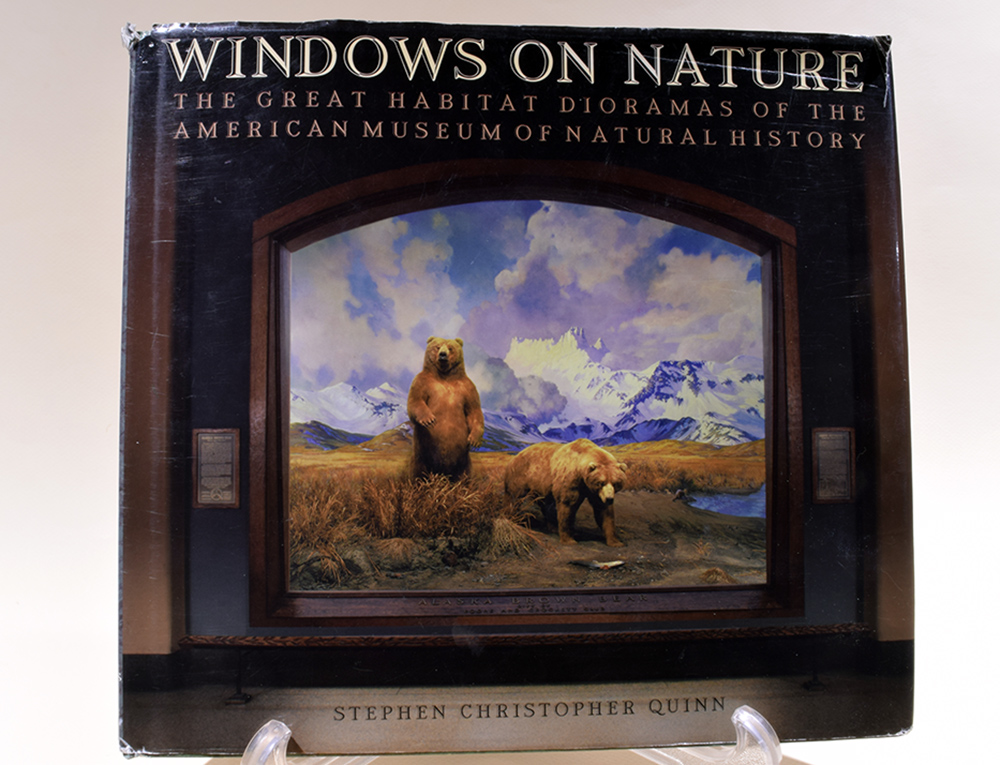

My philosophy is to seek inspiration from the best examples I can find. One such source is natural history dioramas, which led me to the book: Windows On Nature- The Great Habitat Dioramas Of The American Museum Of Natural History by Stephen C. Quinn.

The book covers the background and history of how the dioramas came to be along with their purpose as educational tools. It’s a lavishly illustrated volume that covers more than forty of the displays, with insights into their construction and unique challenges. So how can museum dioramas with stuffed animals help us build model trains?

Context Matters

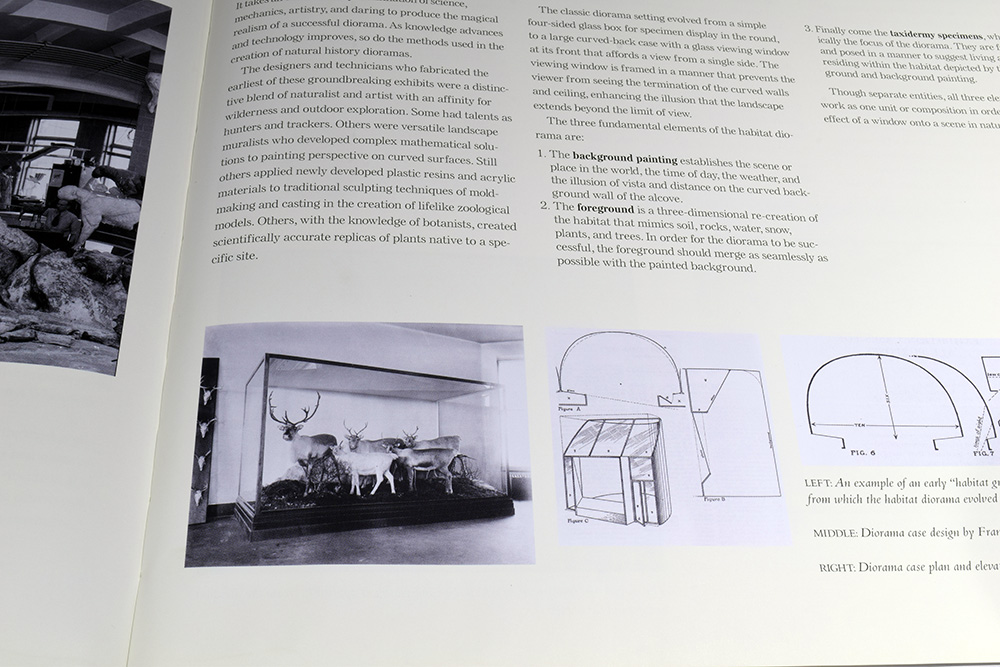

The diorama format that these displays evolved from was born at a time (the late 1800s through early 1900s) when the public became aware that wildlife and wilderness are not unlimited. The dioramas featured in this book were built in the first decades of the twentieth century and are a step forward from the simple taxidermy displays in glass cases that preceded them. As educational tools the context and setting of each of the habitat diorama matters. Each depicts an actual location at a specific time of day. Museum naturalists, artists and researchers traveled to each habitat and did extensive studies of the wildlife, the geology and plant species in order to accurately reconstruct the environment back in New York.

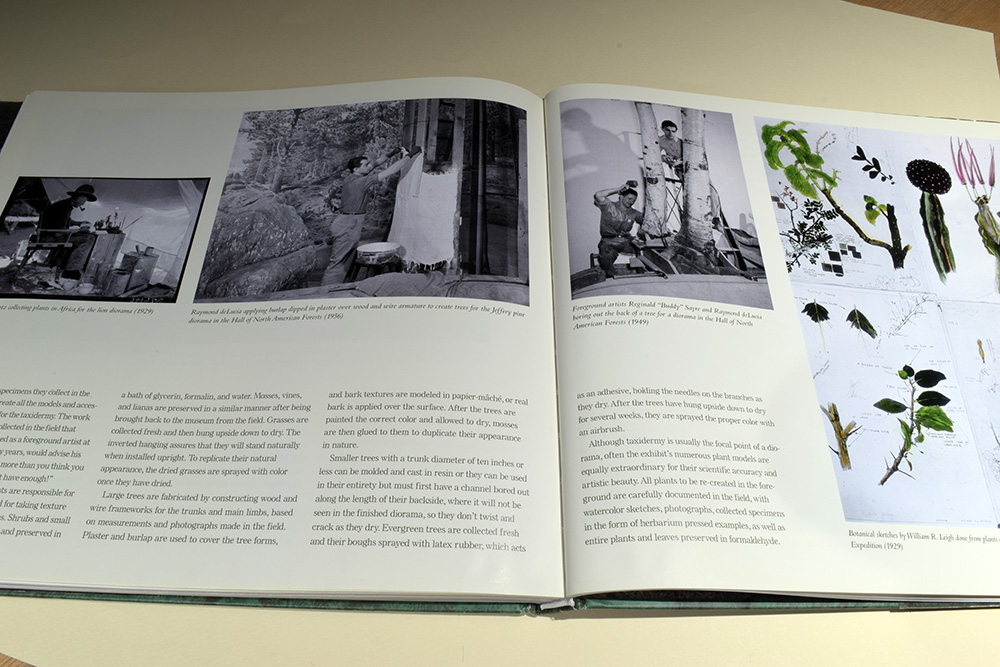

On site, they collected samples of plants, soils, rocks and anything that would be relevant to an accurate depiction. Museum artists took extensive photographs and painted studies noting the terrain, color and light conditions. These trips were arduous and spanned weeks, even months in an age before the convenience of modern travel as we know it.

For teaching tools, such rigor is expected. As hobbyists though, we gloss over the value of such efforts with the lame excuse that we’re only engaged in self-directed entertainment. For many of us that’s as far as our thinking will ever go, yet on some level we understand the importance of context for our models. If it’s as unimportant as some would suggest, then why do we bother with any form of scenery at all?

Small Spaces Can Feel Large

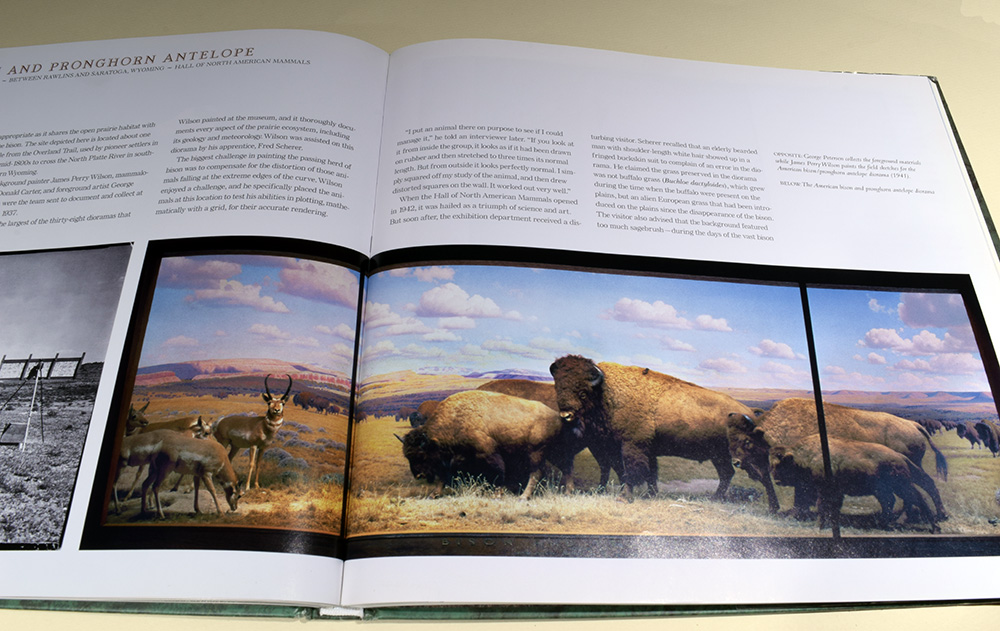

These dioramas are not small-scale miniatures. The taxidermy specimens are life size, yet the actual foreground spaces they occupy are fairly small in comparison to the expansive views they convey to visitors. The secret to the panoramic depth and feel is in the skilled hand painted backdrops and overall composition of the scenes.

Museum artist James Perry Wilson reinvented the art of background painting with his work on these dioramas. His skill and sense of color and space created landscapes of incredible depth. What isn’t apparent to the eye from the photos in the book, is that these background paintings are actually a curved, nearly 180 degree arc. To render a scene in perspective that mimics what the eye sees in nature, Wilson developed a grid system for laying out the composition that compensated for the distortion of the curved surface.

His location and field studies became the primary reference source for faithfully creating the diorama’s background. Wilson spared no effort in his quest for accuracy. To produce the impact of an expansive domed sky, he applied up to 31 bands of graduated colors, carefully blending them together to create a seamless transition from the deep blues at the apex to the warmer tones of the horizon. As the painted landscape comes forward the colors and details blend seamlessly into the 3D foreground. This is landscape modeling of another caliber, yet it offers us many lessons.

The Whole Is Greater Than The Parts

For example, I’m in awe of how integrated the foreground and backgrounds are in these works. The careful blending of color and detail eliminates the clumsy transitions that we see so often on layouts. Their impact has nothing to do with whether the backdrop is photo-realistic or impressionistic, painted or not. It comes from paying attention and from seeing the modeled scene as a whole, rather than a collection of parts.

We are conditioned to think of a layout as a bunch of pieces or a series of tasks to complete before the fun begins. With this mindset we leave the impact of the whole to chance. Our scenes might work together but most likely we have to modify things on the fly as reality intrudes.

What draw me to these dioramas are the same qualities that draw me to cameo layouts: the way all aspects of the design work together to create a believable slice of reality. Thinking in terms of how each element relates to and influences others, brings a cohesive feel. Everything fits and seems in its proper place. We sense an order and intention at work whether we can articulate that feeling or not.

We wouldn’t think of slapping a freight car together willy-nilly from a bunch of random parts (well, narrow gaugers excluded), yet we do just that with the context we place our models into. A blob of plaster is good enough for a rock; a hunk of cotton will do for a tree. Don’t sweat the color, just slather on some gray or green and call it done. Works like these show what’s possible if we can expand our imaginations to embrace the ideas they embody. Is it the right approach for everyone? No, of course not. For those who aspire to better modeling though, there’s no better example except nature itself, to study and learn from.

Regards,

Mike

‘For those who aspire to better modeling though, there’s no better example except nature itself, to study and learn from.’

Exactly.

I have quoted that small piece, but the phrase “aspire to better modelling” is a lovely piece of wordsmithery and frankly not only close to my heart, but balm for my soul!

Today I have been called a “finescale policeman” by an editor of MRJ (the irony doesn’t escape me) for having the temerity to suggest that we each set our own individual standards and assess our own work – no one else’s – against those standards. Still, at least that was done in public: earlier this year I was called “finescale Taliban” in private on a forum, without any real cause in that case. Still, it gave Trevor Marshall an opportunity to put his photoshop skills to good or at least humorous use. And no, I am not sharing that publicly!

Sadly, I think the very idea that we should set ourselves targets and standards – to me the very essence of finescale – is what creates opposition to the idea. Well, I ‘m sorry, but I don’t want to settle into mediocrity in any aspect of my life – and I am not afraid to say so!

Branching out into other hobbies, studies and crafts has always been one of the things which separates model railways from other hobbies: creating a believable setting for authentic models demands this, but doing it well requires greater depth of understanding.

You make that point very well, my friend, and once again I am grateful that we have a forum (in the broadest sense) to discuss this and what it means.

Simon

“Sadly, I think the very idea that we should set ourselves targets and standards – to me the very essence of finescale – is what creates opposition to the idea.”

Simon, you bring an interesting point. Much of the opposition probably comes from the fact many people thinks setting “standards” means “unreacheable standards”. Even low standards, if well implemented, will bring coherence to a project and make it much better than having none. This is probably why we feel so uneasy when we see a great modellers able to replicate perfectly a particular locomotive yet faily to provide it a fitting context. This lack of standards for the whole project really undermines one’s efforts… ruining the best parts in the process. Like any learning activities, I would expect someone would raise its standards with each new project as skills and confidence are built up. The moment a modeller considers he is doing finescale modelling, I understand his standards have been revised quite a few time to reach a certain level. From that point, as you clearly stated, each is responsible for setting its own standards whatever they are. As long as they provide a workable framework, coherence and a way to find satisfaction in one’s work, they have lived up to their purpose for someone who wants to be better at something… anything.

Matthieu,

That’s exactly right. One extreme of standards is exact scale, which is not really possible as prototypical clearances, scaled down, become interference fits and even a simple layout in H0 would require 15’ radius curves.

The latest MRJ contains an editorial which falls right into that misapprehension, conflating finescale with exact scale, and pointing out the need for “compromise”. Well, I don’t like that word, as it usually means failing to satisfy any party and prefer to think of a trade-off, but I shall use it as what is finescale if not a compromise between the demands of exact scale and the reality in which we operate?

This applies to anything in life: set yourself a standard for the quality of whatever you do, and don’t accept anything short of it. Occasionally review and revise those standards – including the possibility that the standard is too demanding and preventing anything from being accomplished.

I think I lead a finescale life…

My first thought – I would bet that the Disney Imagineers had this book on their shelves for reference when creating many of the attractions at Disneyland and the 1964 World’s Fair. The now famous panorama of the Grand Canyon came out of that period, and it in turned influenced many other attractions that rely on a mural type backdrop to create the illusion of vast distance. One of my favorites is an extinct attraction from EPCOT Center’s early days, Horizons. There are many ride-through videos on YouTube as well as images out there that demonstrate the importance of a sweeping curved backdrop. And, in the particular case of Horizons, there were a couple of intrepid ‘explorers’ who got out of their ride vehicles and hid beneath the scenery in order to film and photograph the ride from, literally, behind the scenes. This is not to be done and I don’t endorse it. But, it serves to show some of the technique behind the magic.

My second thought – as scale diminishes, perhaps our technique should change to use, say, broader brush strokes? The choices we make to use a ‘finescale’ technique probably vary from scale to scale just as our expectation of what level of detail is present changes when viewing a large N scale railroad vs a small 1:35 scale diorama. But to your latter point, whatever level of detail we choose to apply regardless of scale, the overall effect must be a coherent whole that all hangs together. We can’t rely on copious detail parts scattered about to carry the weight of the impact the scene has on a viewer.

In my own case, I am taking time to gather my thoughts on ground cover colors, the size and type of balast, the mix of foliage types, shades of rust on the track, pavement texture and color, etc. before I begin the scenic work on my railroad. I will begin with basic shades and work to bring it all along together before tuning in on any particular detail, a bit like an artist may paint in rough shapes and shading before focusing in on a face or sleeve or piece of fruit.

Hi Galen,

I agree the relationship of scale to the level of detail applies just as much to scenery and backdrops. It’s an excellent observation. I’ve never worked in N scale, so can’t speak to those concerns. I do note a difference in my approach between HO and quarter-inch in doing foreground scenery. I’m more aware of the textures in the larger scale. As for backdrops, I think a great deal depends on what you’re representing. An expanse of sky with distant scenery can be quite simple in any scale, whereas a more detailed close-up scene requires more thought with regard to scale. There is no one size fits all solution. Does it look right and enhance the rest of the scene is the most important question I can think of. Your idea of looking at everything as it relates to the whole is a great approach.

Mike