Why would you model track like this? Seriously, why would you choose this route over, say, commercial track that you could slap down in a fraction of the time and call it done?

A lot of people tell me they would love to have track like this but it’s too much work. They want the product without the process involved in producing it. This is the new culture of our hobby.

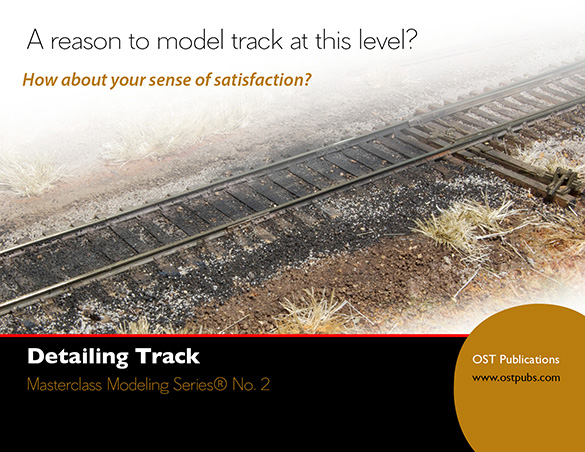

This track didn’t just magically appear. The elves didn’t come in overnight and do it, nor did the tooth fairy. It’s the end result of a multi-step process that was practiced for many years. A process that saw false starts and outright failures, and yet was repeated over time until I could produce the track seen in the photo as a result of learning and staying with that process.

That statement should be self-evident, but apparently it isn’t to a growing number of people who now believe the hobby is all about an end result (the product) instead the process required to bring said result into the real world. Like I said, the distinction between the two should be obvious. Don’t you think?

My reasons for handlaying track to that degree of detail are the only ones I can speak about with any authority, and they revolve around my sense of personal satisfaction that is hinted at by the second question in the photo.

Since I’m largely preaching to the choir here, and since several of you have told me you’re tired of my harping on craftsmanship and such, I’ll simply leave you with the question instead of belaboring the point. However, it’s important to review and be reminded of certain principles in this craft. It’s very easy to let others do your thinking for you in this hobby and a solid grounding in what this craft actually is helps to internalize those principles to the point that they feel natural and become second nature.

All that said, for now I’ll just invite you to look at the track in the photo again and consider whether it’s a result you’d like to see on your layout and whether you’d like to learn the process involved in creating such track. If so my book, Detailing Track, covers it well.

Welcome

If you’ve come to this blog for the first time, then let me welcome and encourage you to look around. But if you’re coming here with your mind already made up, if you only want easy answers and you don’t care about the opening question or think it makes any difference to your experience of the hobby, then this blog isn’t going to be a good fit for you. I don’t practice a commodity hobby or seek simplistic solutions. What I do here and in my books is encourage you to challenge your assumptions, think for yourself and fully understand the “why” behind the choices you’re making. I don’t mean to offend anyone. I just think it best to get that clear and out of the way so we aren’t wasting our irreplaceable time. This blog is about the process, not the product.

Regards,

Mike

It is the harping on about craftsmanship that I come here for!

I’ve just had a long chat about why I’m hand building my track using C+L components rather than using copperclad “because then you could get it done quicker.”

That much is true, but then I would also always be looking at it thinking “That doesn’t look right”

Regards

James

What he said.

Simon

Not to worry gentlemen, the harp section of this orchestra isn’t going anywhere.

Regards,

Mike

Mike,

My prototype is rather old and in need of lots of maintenance. The jointed rail has shifted over time along with the supporting ties. The only way to properly model it is to duplicate it piece by piece. Flex track just doesn’t cut it.

I am aware of one other who models the same prototype and he used flex and sectional track in HO. Although he seems to have a good eye for some of the structures and scenic elements, the track looks weird. Photos of it only emphasize the perfect spacing and over size tie plates, etc.

My own view is that if we can’t get the track right, then what ever we do beyond the track cannot make up for an ugly shortcut method.

So, to answer your question; my chosen prototype demands it.

Ben

Thoughtful commentary as always, Mike. And your question applies to all aspects of the hobby – whether it’s modeling track, creating scenery, building a structure, or bringing a layout to life through realistic operation.

Any of these endeavours requires a lot of work to do well – in various combinations of bench time and research.

Doing track to the level of detail you’ve demonstrated requires research to understand the prototype… photography to capture examples… experimentation to replicate it in miniature… and then time to distress ties, add joint bars, spike every tie through tie plates, and so on.

Recreating a given prototype’s operations requires less time at the bench, perhaps – but still requires research… time at the computer to create the required forms, rulebooks, timetables and so on… and experimentation to adopt the prototype system to the layout in a workable, realistic manner. It may also require bench time to create the physical tools required to conduct operations: On my layout, for example, these include replicas of the waybill boxes, slide out work stations to help conductors organize their work, and a working telegraph system to OS trains.

While these endeavours all require drawing on the expertise of others – for example, reading your book on track as part of the research phase – they also require individuals do their own thinking. Again to build on your example, faithfully replicating the track that you have created only works if the reader is building the same kind of railroad that you have. The type of track one is required to model depends on the economic health and corporate culture of the prototype being modelled. It also depends on the era, the region/terrain through which the line runs, the weather/temperature/rainfall/snowfall and other environmental conditions and other factors – including, as we’ve discussed privately, the idea of deviating from reality if it helps to tell a stronger story to the viewer.

I really like your phrase, “Learning and staying with that process”. I too am intrigued by process, and on my own blog I’ve referred to myself as a “process modeler”. I do a good job, I think, at the first part – at learning a process. I still need to work on staying with it. I find the process of solving a problem (e.g.: building better track, building a better tree) really interesting and I enjoy the first successful examples that I produce of something. But I grow tired of repeating the same process over and over to create more examples of the same. (The first three freight cars? Great! The fourth, identical freight car? Good. The fifth and sixth, identical freight car? What else needs doing?) I tackle this problem three ways.

1 – By being aware of it.

2 – By spreading out the process. Instead of building six identical freight cars in one go, I’ll do the first three – then do other projects – then return to build the second three.

3 – By building a relatively simple layout. I can sustain the momentum to build what I need for my layout because it’s easy to see the end in sight. For example, the layout has eight turnouts – so when I got the first two built, I realized I was 25 percent of the way to “finished”. That encouraged me to do the remaining six. I’m not sure what the breaking point is but I know that if I had 100 turnouts to build – not unreasonable for some of the larger layouts in the hobby press – I’d get the first two done and realize I was only two percent of the way to my goal. At that point, I’d probably be looking to see what’s on TV…

I like the harping. Keep harping.

Cheers!

– Trevor

What I do… …is encourage you to challenge your assumptions, think for yourself and fully understand the “why” behind the choices you’re making.

For a lot of modellers – for a lot of people – this is heady, and scary, stuff. It runs counter to the “bread and circuses” comfort zone which is spoon-fed by much of the modelling press, including the web.

The “why” is a big deal: trying to model North American railroads from the UK can be quite demanding, as the differences appear to be manifold and quite alien. But they are only on the surface, and largely reflect the natural consequences of building railways to open up new lands across a whole continent than for improving the speed of commerce between major industrial centres on a small island. Once I got my head around some of the reasons, a lot more made sense, and my appreciation for the prototype has been enhanced considerably. A railway is still a railway, regardless of how it is operated.

It is also clear that many (most) modellers don’t even get some of the basics right. Putting aside the use of ready to play sectional track in terms of fidelity to the prototype, it is still possible to operate more realistically. The real railroads don’t ram freight cars into each other and then immediately pull back: they pause to align the couplers, make the connection, check that the pin has dropped and maybe connect up the air hose and do a brake test. Neither do they stop some distance short of the final destination when switching, pull back slightly to disengage the couplers, then push forward again. Give me the “hand of God” over the “magnetic coupler shuffle” any day…

Thankfully, not only are there sites which do contain the required information, but these sites also demonstrate how to accommodate prototype features into the compressed space in which most modellers operate. I can mention you, Trevor and Ben as excellent examples of this, but there are many more.

A Quaker Friend of mine as a wonderful and subtly ironic way of putting it:

“Thou shalt. …think for thyself!”

As I said, scary stuff to some!

Simon

Simon,

The converse of “think for yourself” seems to be “copy what other modelers have done.”

That isn’t always a bad thing, of course, but it is when it distances us from the prototype. One of my current bugbears – I have more of them as I get older – is modern image UK layouts that seem to just copy cliches from other layouts.

I think the likes of Chris Nevard, George Dent and Phil Parker have done much to significantly raise the floor of what the average UK modeler should achieve as a starting point , but perhaps they aren’t raising the ceiling of what others should aspire to.

I’m sure many modelers just want something that is good enough to complement their RTR stock. What makes people move on to the next stage is, I suspect, not easy to pin down. In my own case I think there were two key factors. One is that in choosing to model a very specific prototype and location small details become important. You find yourself asking very specific questions. The other is the increasing standard of model railway photography on the web and in magazines, which means that detail, or the lack of it, that would have gone unnoticed a few years ago is much more obvious. ,

Very thoughtful comments gentlemen, as always. It’s been a busy time this week, I’ll respond more fully in due time.

Regards,

Mike