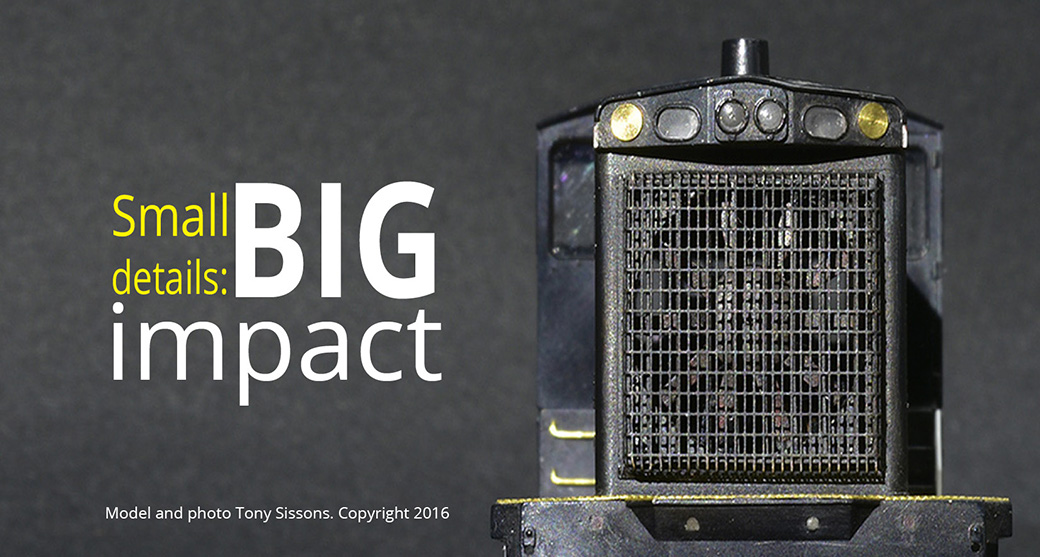

Small Details: Big Impact

It’s no secret to you guys that I like fine details. My understanding of the world is filtered through such details. Yet I understand why people think my focus on individual details is misguided, when the objective is to have a large layout or an operations oriented approach. To get bogged down in a sea of individual details is at odds with both preferences.

I want to suggest that there is more to consider than individual details on a single model. While these are important for the quality they bring to a model, it’s also important to understand their impact as a part of the entire scene.

To my eyes, nothing screams toy louder than coarse, over-sized elements. I don’t care if it’s the cast-on ladders of a cheap freight car or window muntins that look like 2x4s, such grossly out of scale features ruin any sense of realism in the model. The full-size items don’t look like that, so why should we settle for them in miniature?

I apply the same question to scenery. Why do we accept out of scale tree trunks, fat utility poles, or loud colors of vegetation? We’re finally paying attention to rail sizes and ballast texture, even in the smallest of scales but, paradoxically, tend to ignore these items in larger ones where the visual impact is far greater.

I’ve featured the work of Tony Sissons (with permission) once again as an example of the impact small details have on our perception of a model. In the opening photo, Tony designed the safety grill for this SW1500 and had it professionally etched and he also scratchbuilt the large fan and the louvers you can see behind the grill. To his eyes commercial grillwork is too coarse and detracts from his enjoyment of the model. As a switcher moving a cut of cars slowly and deliberately, there is time to study the model, and the front of the loco is a prime target for the eyes.

For modelers like Tony and myself, such details are part of a chain of interrelated pieces that together contribute to the quality of the whole layout. A properly detailed loco, running on properly detailed track, through properly detailed scenery conveys far more realism than an out-of-the-box model on over-sized track through generic out-of-the-bag scenery ever would. Our eyes and minds know the difference between the two. We know when something doesn’t look right or when a critical detail, large or small, is missing.

It’s easy to look at Tony’s work and feel intimidated, thinking that it’s fine for him to go to such lengths because of his experience. This is a very real feeling we all have because of our tendency to compare the finished work of an accomplished modeler like Tony to our own in process mess. In doing so we’re not being fair to ourselves.

It’s more productive to look more closely at your prototype. If you’re genuinely serious about improving your skills, you need to consider the depth of your understanding. Do you really know the subject you’re modeling? Do you understand the relationship of one piece to another and how both influence the whole? Where your working skills are concerned, are the cuts well made, are the parts measured accurately? Is the assembly clean and tight? Answering such questions puts your focus on the work, which you can influence, rather than on someone else’s work that you can’t. Experience comes over time via lots of observation and exposure to the prototype and to fine modeling. In time your eye and judgement become more refined. Learning to see the difference between coarse and fine details, is within the reach of anyone willing to make the effort and OST Publications is here to help.

Regards,

Mike

Not surprisingly, I agree.

The importance of finesse of work and squareness (or whatever angle is appropriate) can never be overstated. Work which is clean and square looks good, and reveals real craft and graft.

As you say, this can seem incompatible with building a “basement empire”, but given the advances in the level of detail or ready to run equipment – now that manufacturers have realised that the real money is in the serious adult side of the hobby – this is no longer the issue it was.

I often hear of the “three foot rule”, the “five foot rule” or even the “end of the garden” rule. To me, these concepts are often abused in the same way that “good enough” is misused: the latter really means “fit for my defined purposes”, not, “I couldn’t be bothered to try harder”. I have no problem or issue with the “three foot rule”, but to me it means that rather than modelling every single clevis and linkage as separate pieces, a piece of wire or an etching can be used, with a few extra pieces here and there, to suggest more detail than is there. This still requires that the workmanship be clean and square, and the parts be fine and not simply moulded: they need to catch the light.

One of the biggest problems is with texture. We now that, for instance, there is depth to the mortar line between bricks, and that brisk usually have a slightly rough surface, yet when scaled down, this is unnoticeable apart from a Matt finish as the light is scattered slightly by the surface when it is reflected. So rather than filling mortar courses with spackling compound and dry-brushing the surface, we see over-deep grooves which are a caricature of real life. And don’t get me started on overdone relief for stonework, yard dirt and ash surfaces, and especially “distressed” timber… Martyn Welch once told me that his most effective weathering projects involved him spending more time on removing the previous application of paint, as he cut back the effect to make it more subtle.

Yet I see adverts for “craftsman” kits, awards given for excessive relief, and rapturous on-line fawning for models which, if translated to full size, would see the subject matter fall apart. This is not weathering, but severe erosion!

As well as clean and square, the texture needs to be fine and discrete – a little bit of texture, maybe, but a lot can be suggested with paint, too.

I think Tony’s work exemplifies this approach. Nothing is overdone, nothing is over-heavy.

Simon

After spending 8 years of my life working for the railroad, the one thing that I walked away with in the hobby world is details, details. Things that seem an everyday occurrence to an engineer immediately pop out if they are wrong. For example, I see (in 1/29) locomotives being run with locomotive brakes applied (piston is all the way out, brake pads are way to close to the wheels), glad hands messed up (train line is the largest, followed by the main res which is slightly smaller, followed by the even smaller actuating and independent lines), hand brake chains tight when they should be loose, etc. Granted some of these details are only seen by the professionals, but in my mind they stand out. A friend of mine and rail pointed out that he doesn’t like sound in his model engines because he notices all the tiny errors that are missing from a typical prototype engine.

The more you know and pay attention too, the more you notice missing from the modeling. That’s one reason why I model in such a large scale to faithfully replicate the details that I notice are incorrect.

When I first saw the picture of the SW1500, my mind immediately when back to climbing aboard one to work the nightly switch engine. Climb on the back, and the fan is idling, shutters open and shut. The engine is alive time to go to work…

Craig

My apologies Simon. I’ve been distracted these past few days. you make excellent points as always. your observations about texture are spot on. It is often overdone and coarse. A technique will appear in the magazines or online and it’s off to the races as everyone tries to copy it. Another area where we can do better in with rendering color. We all use the same brands of paint and, coupled with copycat techniques gives the craft a homogenous appearance. Sort of like seeing the same fast food franchises and big box stores everywhere you go. Distinctiveness is lost. What I like about Tony’s work is it has his stamp on it even though the foundation is a commonly available piece of kit.

Regards,

Mike

Hi Craig,

There are details only an experienced pro will understand and appreciate. That’s why I value your contributions to our understanding. I’m not crazy about sound anymore myself. It’s too loud in most cases for my taste.

Regards,

Mike

Mike,

I agree that sometimes modelers turn up the volume way to much but that said, the typical cab interior is around 60-80 decibels. Most new locomotive cabs are “quiet” and are limited to the 70 decibel range inside the cab at notch 8. I have no idea what it is outside the cab but I’m guessing it’s more in the 80-90 plug range. Very loud after even a short amount of time. Now I’m not sure how one could scale that down and take into account how far way in scale feet the decibel range should be for a typical operating session, but with more than one or two engines it still would get quite loud in an enclosed space.

If found this pdf that explains how loud things ‘should be’. A lawn mower is typically around 90 dB.

http://utu.org/worksite/PDFs/safetylawsummary/NoiseEmissionStandards.pdf

Craig

It doesn’t take much noise in a basement to be uncomfortable.

Mike