As much as I’ve sung the praises of shadowbox construction, my tastes are moving toward simpler forms. Even though there is a lot to love about the shadowbox format, looking at Mill Road today the eight-foot long x 24 inch high modules seem clunky and overbuilt to my eyes.

In this stage of life, I want less complication, far less stuff and more time to enjoy what I have right now in terms of this craft. I know what makes me happy in it and I want less impact on the resources devoted to a layout.

There are features of the shadowbox form that I do appreciate such as the integrated lighting and backdrop and the way the upper and lower fascia frames the scene. There are drawbacks such as extra weight and the bulky mass makes storage a challenge. I’d like to have a series of modules that I could switch out for variety. However, eight foot modules take up a lot of horizontal space. I could strip the existing scene down if I wanted a change but that seems like a knee-jerk solution that still produces a lot of needless waste.

Continuous Design Is An Evolution

This is another step in a direction I’ve been headed toward to define (for myself) a different kind of layout form. One that could fit more easily into the home. One that can adapt to a range of spaces with less disruption and waste than the traditional stick built construction the hobby has been married to for decades.

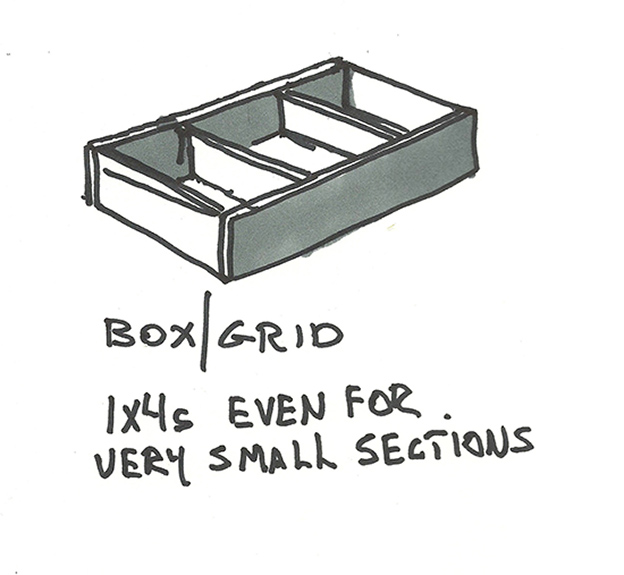

(Above and below) Is this much structure and heft really necessary? I no longer think so.

Doing Away With The Box

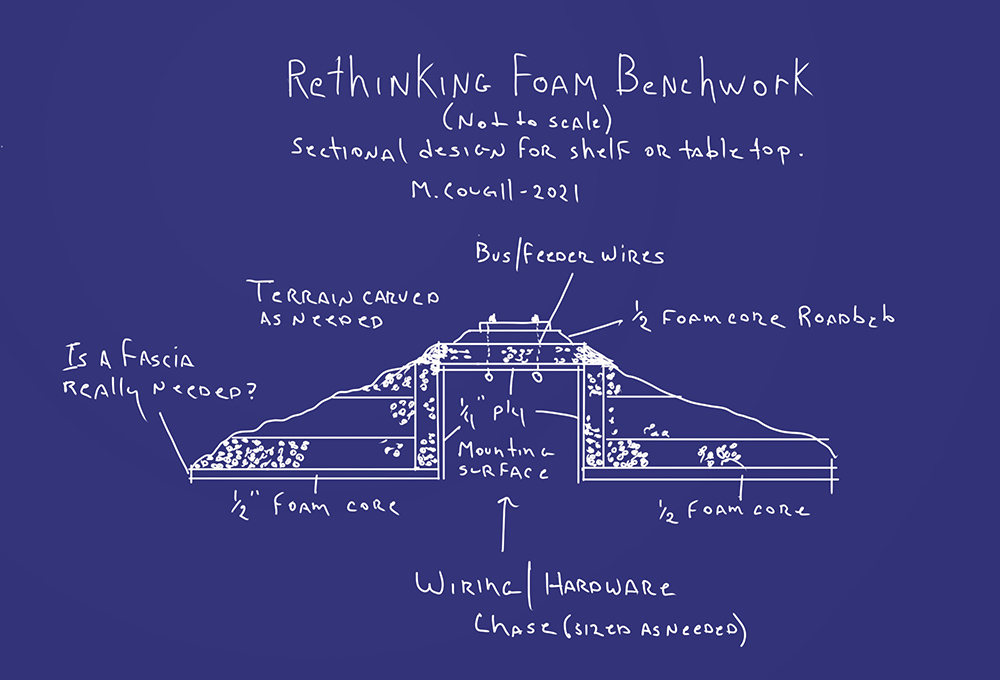

I experimented with this form a couple of years ago (photo below) but never pursued it beyond this test section. (Full description here.) I think there is a lot of promise in it for a lightweight and portable form that would be easy to set up and store when not in use. Although I show a single track on a low fill, that was a proof of concept to include scenery below the track, and move away from the flat slab mentality.

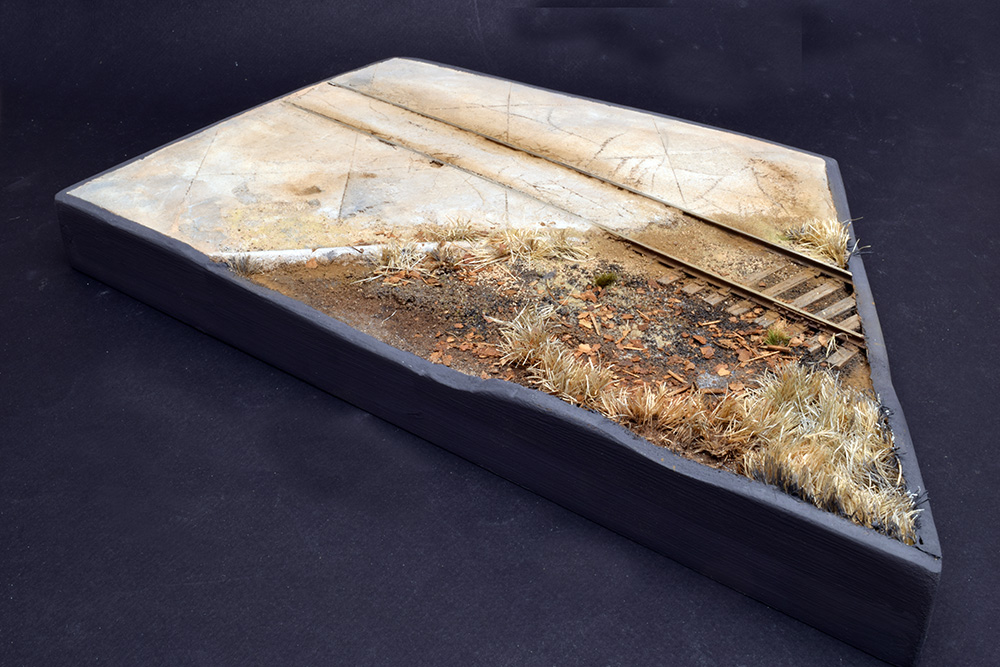

Another experiment produced this simple diorama with street trackage. I described the design process in this post. I eliminated all of the traditional construction materials and methods by laying the track directly on a piece of expanded polystyrene foam board. I wanted to see how handlaid track would work on such a surface and I’m convinced it’s viable. While this study is quite small, larger sections that link together are entirely possible. Depending on the scene I choose to model, I’m leaning toward a hybrid design of the two going forward.

My Personal Design Brief

I envision modest, lightweight, portable layout scenes focused on switching that could sit discretely on a shelf or similar flat surface in any room you choose. They could be left out for permanent display or stored away until the next operating session. I’m thinking along the lines of a layout as furniture or even room decor: something added to a space and arranged as needed, rather than a permanent installation that requires a dedicated single purpose environment. I have in mind apartment dwellers, condominium owners and similar situations where structural changes to the room are not feasible or desired. I envision a series of modules or scenes that can adapt to a range of room sizes and configurations, much like the concepts that Iain Rice proposed in his many books.

*I’m also committed to P48 modeling.

My experience of railroading is firmly rooted in Midwestern standard gauge subjects and I’m not interested in starting over with a different scale or track gauge.

*I want to approach each scene as an artist would in terms of visual composition.

I’ve found conventional track planning isn’t going to take me where I want to go. I want realistic scenes rather than tightly compressed caricatures. No. 10 turnouts are completely viable in a small scene as Mill Road demonstrates. It should go without saying by now, that quality matters far more to me than quantity. I’ve realized that I need far less layout to be content than I once thought.

*Lightweight materials and construction are a must.

We build layouts as if they are an extension of the house itself; a custom designed rock solid assembly that will be there forever. This approach makes change hard to do without a serious amount of downtime and waste. Others are free to make that choice but I’m over it. To the degree possible, I want to eliminate wood and other dense, heavy materials like fiberboard roadbed. My experiments show they aren’t necessary for smaller designs. I do prefer the durability of quarter-inch (3/16″ actually) plywood as a fascia material but want to minimizes its use over large areas.

To be certain, this is a very specific set of criteria that won’t work for every taste or subject matter. My focus is on the quality of train movements rather than the quantity. The layout concepts I enjoy most are those designed for solo operations at a moment’s notice, rather than large group marathons.

I don’t haver any specific plans or dimensions to give for now. I want to take time and play with these concepts on paper some more. I do know that a 15-16″ depth is the sweet spot for my needs. I also know that the module length will vary according to the scene. Four feet feels like the obvious default choice, however for the rental spaces mentioned earlier, it may be the most flexible option. For a home setting, I would consider a six-foot length as the maximum in terms of storage. Having said that, please let go of the idea that these are hard and fast dimensions. You may only have six feet of available space in total. I suggest that module design be as flexible as you care to make it.

Small Layouts Need A Different Mindset

Small layout design is an art form of its own. It requires a different mindset and focused choices. Resist the temptation to compress the hell out of everything in order to stuff more in. A solid design embraces the constraints and challenges no matter how severe they may be. It’s important that your expectations are clear and realistic in terms of what you can include. That’s where most of us fail. We invariably want more layout than the space can realistically support and it’s time to be honest and admit that.

I’m not proposing anything new here. Modular layouts have been around for decades in some form or another. If there is a difference its in the framework and experience I bring to the subject. It’s also in the willingness to question every sacred cow assumption about what a layout is or has to be. It’s in breaking the strangle hold that a layout’s size determines its value has on our thinking and choices. In exploring these ideas I think as an artist first and foremost. Next time, I question the assumption and need for a sky backdrop.

Regards,

Mike

Mike,

There’s a long list of threads on MRH forum about foamcore benchwork. The biggest proponent of it has built quite a few modules of various sizes and shapes with nothing more than foamcore, a #11 blade and hot glue.

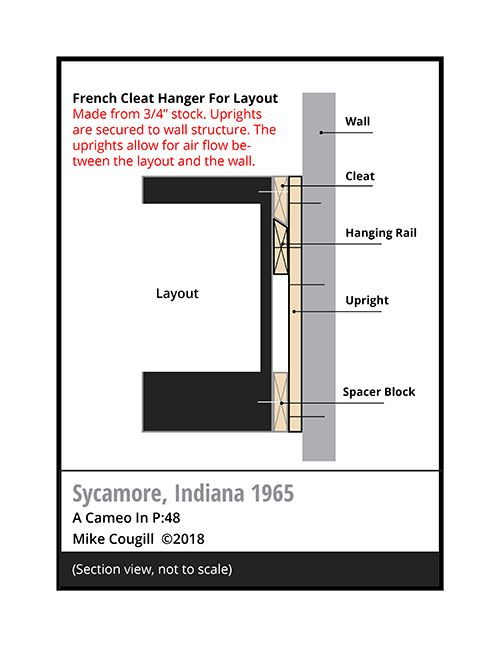

A foamcore framing would certainly be lightweight but yet strong enough to move around from storage to display. It’s overall weight might allow for a French cleat style system of 1/4″ ply.

I love this conversation. I always feel like I could retire to live comfortably, satisfied, in the space you nurture here.

We have this untested assumption regarding benchwork that is so wildly overbuilt and it seems our revisions to it only make it more complicated. I think back to the various guides and standards I had in my studio, as references for designing case goods (like cabinets) or similar architectural millwork. Divorced from all our passion, what we’re making, when we make benchwork, is simply a shelf to arrange some models on. If we didn’t have a layout these same models would sit on a bookcase in our living room, maybe alongside favourite books or music. Those bookcase shelves wouldn’t be L girders spaced at wall stud centres. Somehow when we take the trains off that shelf and put them on a layout their physical properties change. It’s weird eh?

My design intuition is tempered toward smaller scales, like my beloved N scale, but I believe this to be true: in addition to the structural mass created by the way we build the layout’s frame often adds more visual mass than its purpose contributes into the space. We don’t notice the visual mass issue in a basement or room-sized layout but in a shadowbox style layout that shares space in a common room in the home our design for the typical shadowbox creates this visually heavy object that minimizes its contents to the role of things discovered only by the dedicated explorer. N scale trains are about an inch tall. On a piece of tall roadbed “mainline track” maybe that vertical dimension doubles. Still, it’s a thread-thin band of visual interest whose voice is easily lost against a two foot tall backdrop and framed in a fascia-wrapped container. Your thoughts on sculpture presentation come to mind here and I’m curious how we can alter our design to make a feature of our models within the space? It is them, after all, why we are doing this.

We live in an apartment now and I miss my workshop and its tools. Part of the apartment matrix is considering ways to minimize damage to the site but also how I don’t have access to layout tools like my tablesaw or space to swing sheets of plywood around. A fascinating part of this discussion is an exploration of alternative framing designs married to those alternative structural members and how we can use them when our tools are simple handtools and our worktop is the dining room table.

My minimalist nature presents alongside my environmental sensibilities here too. In refining the design of this structure we reduce the amount of material invested into the form. In the short term this saves a real financial cost to the modeller. As our interests move on, or we ourselves do, refining this lightens the load that will be dumped into a landfill. (We took what we needed to make this and understood what it would cost to give back)

Last year I had this vision for framing a layout (my Wing concept) that was based on my memory of how model airplane wings were framed. At that time the dimensions of even entry level gas powered models (example: Carl Goldberg’s Eagle “trainer”) had wings of a shape like our 1×4’ small layouts. That wing holds the airplane in the air for flight and its design is bound by finding a balance between structure and weight. I liked that basic idea of ribs connected by a central spine both for the reference and also that, well, we’ve tested it in flight. It’s abstract to see that model airplane wing as a model railroad benchwork until we let go of the terminology.

My current thoughts start at the surface of the ground. What’s needed to support that crust? Could we make this over a temporary form and as the model earth’s crust hardens could we remove the formwork leaving behind only the surface? (Imagine lifting a hardshell mountain off a layout)?

I love this line of contemplation and look forward to thinking about it more.

Chris

I find I really like foam because it can be worked with ‘apartment life tools’ like a utility knife and bonded with simple adhesives (my current favourite for bonding foam-foam or track-foam or cork-foam is those inexpensive low temperature hot glue guns).

Foam is fascinating though because while it’s easy to work the process is a subtractive one wherein we’re taking material away and we visualize or develop the scene in an additive way. I wonder if there’s a better way we could be using sheets of foam that stacking them like cake layers or books on a shelf?

Chris

Hi Chris,

Your points are well taken as always. I’m from an era when high quality dimensional lumber was readily available and reasonably priced.In my view, we simply moved from 4×8 foot tabletop layouts to two foot wide shelves that hug the walls. The material choices for both seem divorced from practicality. In old school quarter-inch scale 2×4 or heavier seem to be the minimum standard. I guess such materials might be good if you’re dragging a thirty car train of loaded hopper cars that weigh a pound each, but most aren’t doing that.

It’s not just the materials but the mindset behind such choices. I get the desire for stability across a large layout structure but really? Does an HO or N scale model need an 1-1/4″ thickness of support? (3/4″ plywood plus 1/2″ of roadbed material.) Given the cost of the stuff, and the way we use it, there is a lot of wasted resources being generated. It’s choice I no longer want to make. Granted foam sheets aren’t an ideal material environmentally either and, in many ways, they are worse. For those reason, I have a love/hate relationship with the stuff. It has properties I like but I’m fully aware of the downsides to it. All of this adds up over time and we may never truly understand the overall impact of our choices. That’s a conversation that needs to happen too. -Mike

Hi Craig,

There’s some interesting ideas there.

-Mike