Drawing: Thinking With A Pencil

Drawing came naturally to me as a child. The grownups made a big deal of it but drawing was just something I did for fun. Over time I took it for granted and never developed the discipline or depth with it that I could have. The lost opportunities from that indifference often haunt my more reflective moments.

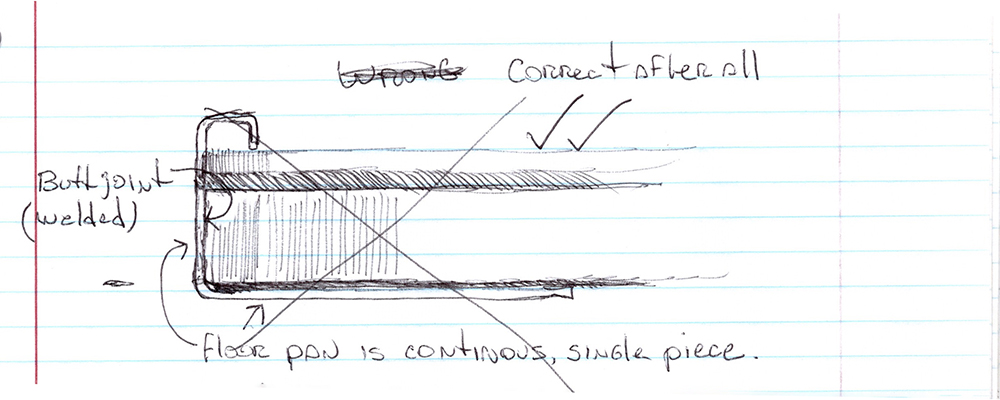

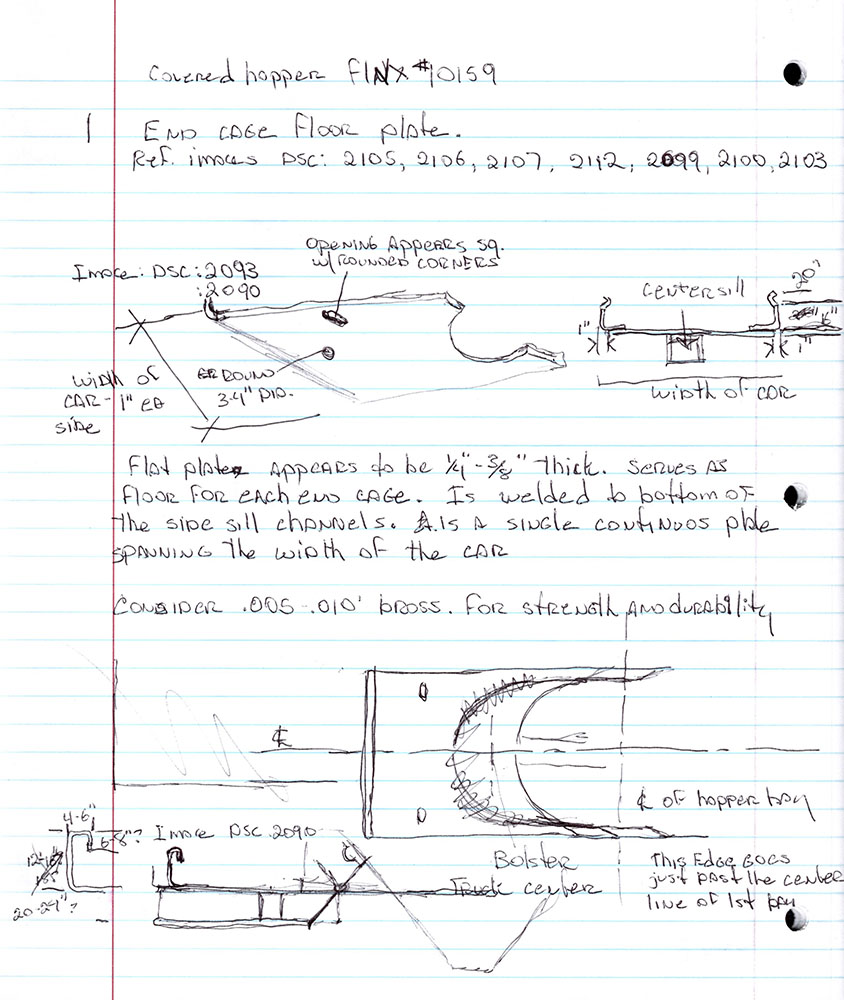

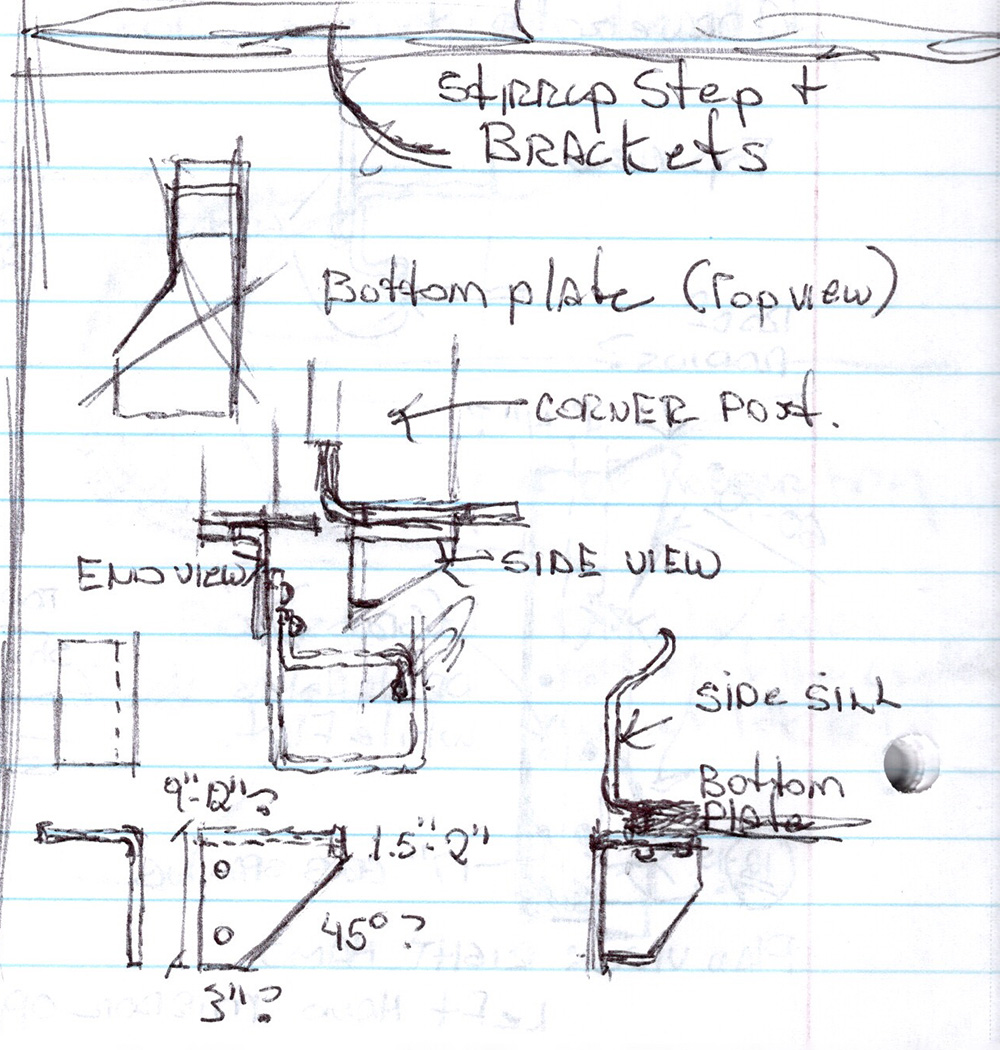

Drawing is a way for me to understand objects. It helps me see the relationships between the pieces of a subject and how they fit together. As I sketch I’m mentally asking questions such as how do these two parts come together? Do they overlap; if so, which one goes on top? Are they butted and welded; is there a mechanical fastening? The more I explore such things by drawing them, the deeper my understanding goes. It may be easier to rely on photos but drawing engages the mind in a more active way. There is a deeper level of observation and analysis in drawing that connects you to the subject in a way just looking at a photo doesn’t.

I’ve made sketches of the details of a covered hopper. Even though I have a good series of photos, with drawing I find it’s easier to see shapes and how a part like a corner post was folded from sheet metal. If the actual part was made that way, odds are I can recreate that method on the model. The drawing process also suggests new questions even as I’m answering others. Combined with the photos, this deep analysis spurs my thinking about ways to model the car more faithfully. I used to look at an object and wonder how to draw it. Now, I look at something and wonder how I would build it.

Photos like this one are profoundly useful and I wouldn’t attempt a build without them. To further enhance my understanding, I also like to draw these details out (images below) as a way to think through the construction of the model.

I could also print out my photos and make these notes directly on the print out. Drawing them however, connects me to the construction process in a tangible way that looking at a static image doesn’t.

A lesson I need to relearn is not to rush this process. It’s helpful to let the initial sketches sit for a time and then review them with fresh eyes. I’ll often discover something new or find a correction to make. In both cases my knowledge of the subject will be better for the effort.

We tend to hinder our enjoyment of drawing with unrealistic expectations that it has to be perfect. As shown here my sketches are crude, made on ordinary notebook paper with a ball point pen. As my understanding of the car grows, I may refine a few of them for greater clarity. However, it doesn’t matter how accomplished the drawing is, it’s what you learn to see during the process that’s important. This isn’t a chore for me as I’m lead into the project in satisfying ways and I enjoy the discovery process that results. Reconnecting with drawing strengthens that through line of creativity I’ve enjoyed throughout my life.

By choice and by habit, traditional drawing tools and methods work best for me. That’s not to say that modern software design tools wouldn’t be the better choice for others. It’s a matter of preference and what works best for your temperament and situation.

When I sketch like this, I’m standing on the shoulders of giants. I’m connected to a long historic line of artists; architects, designers and engineers, who, over many centuries used pen, pencil and paper to better understand the world and themselves.

Regards,

Mike

Coming up in two weeks: Practice makes perfect.

I really like that this is becoming a series of posts.

The old “if you can draw it you can build it” line is such a powerful statement. When drafting architectural plans my job was to translate the sketches of the architect into a language the builder could, in turn, represent in the material of choice. So, those drawings are a translation medium but also a chance to test the design. If I’m unsure how to project a line from within the drawing how can I expect that shape to be rendered in metal or wood? (Draftsman by training but translator by role and it’s that role I continue in even though my profession has moved from the architectural studio to the statistics lab – what I plot ink around has changed in form but my role is no less the translator’s string connecting the hand to the balloon)

When we draw we are testing our theories from the study of the subject. In looking at your drawings I see your notes on how two pieces of material are joined. It’s a way of testing what we know and identifying gaps in our study we can fill with knowledge to gain or at least a decision on how we’ll address “that” when we build the model.

I feel very comfortable working in CAD and draw on decades of experience pushing my mouse around a screen in AutoCAD. It’s ability to accurately render an object in precise detail is a powerful supplement to my creative process just as I enjoy, equally, the amazing CAD tool that Templot is for drawing model railroad track to accurate scale and tailored, as precisely, to my needs. In both cases though, those tools are powerful when an idea moves from concept to production and translating the original sketch into a finished form. But before any of that can happen, I light the fuse with a pencil or pen on paper. I can comfortably analyze and react to an image on a screen but I can’t think or act creatively on screen. For that, I can only breathe on paper. I think maybe that’s now because I “know” that my paper and pencil I’ve divorced from production and defined as being attached to the idea in its conceptual state. Freed from the need to be practical it’s role role is more social and that paper and pencil are the tools of the curious mind exploring the dimensions of an idea.

Like a two step process. Pencil and paper to imagine how I’ll capture a cloud. CAD to plot how I’ll interact with a cloud once I’ve harnessed it.

Chris

…which reminds me of working on Coy and laying its track (my current layout project). I used Templot to translate my initial layout sketches from pencil line drawings on paper to something more tangible. On a stage of paper my pencil moves to connect points guided only by grace. Retracing that into Templot allowed me to leverage Templot’s ability to calculate the location of rails and ties and, in doing so, contribute a filtering layer over my sketch to further qualify it. As you’d note in your work: refinement. Like any good play, there’s an inter-relationship between my hand, my tools, and my work. While I used the intermediary step of tracing the initial pencil sketch into Templot, I didn’t both adjusting tie spacing, size, or locations in the CAD drawing. The estimate of the tie locations along the track and the position of the rails was “enough” to feed that next creative step: building the track.

I enjoy this chance to talk about the tools we use, why we reach for them, and why we might use one or not the other. Our hobby enjoys prescribing a set of tools as the only ones to use and that divorces the craft from the artist but insisting there’s only one tool for that job. This conversation you’re encouraging moves beyond prescription to something more personal and a great deal more rewarding. I’m so passionate about a chance to use model trains as a way of expressing an idea in our heads and talking our tool choices is a way to express, on a personal, artist by artist, level why we chose these tools for this work in an equally important way. It distinguishes your work as an extension of your identity and instills a value into your work that otherwise might be lost if all we ever talked about was a thing you made in brass following a ten step article from last month’s RM/MRJ/RMC/MR/H/RMJ magazine.

Chris

Great post Mike, and comments, Chris. As an artist and professional designer, I draw for a living – and draw as part of my modelling process as well. A pen or pencil on paper is indeed a great way to understand your subject matter and think through a process.

I’ve recently been 3D modeling some 1/24 scale cantilever signals, and upcoming scratch building project. I drew and measured them in the field – it’s amazing how that process instantly brings so many easily-overlooked details to light. Then I start in CAD and 3D, and it doesn’t take long before I realize that what I thought was a fairly complete drawing is missing all kinds of important dimensions – so I mark the sketches with my needs and set them aside for a return visit.

Seeing your notes on your sketches is my favorite part – it’s all part of documenting your thought process. And sketches for the model convey very different information than sketches of the prototype – the translation process that Chris was mentioning. At the end of the day, Mike your initial point about this all hwlping us better understand the subject matter is spot-on. It’s not unlike illustrators sketching skeletons and muscle structure to better understand their subject matter.

You never really see something until you try to replicate it. Drawing is a low-cost, low-risk first cut at replicating. By drawing the subject, you are forced to capture and realize the details that bring it to life. I never thought about this before, but if you reach first for the modelling knife, you risk modelling your way into a corner, where you cannot capture certain details. Thanks for pointing this out, Mike

Thank you everyone for the kind words and the depth of these comments. They make this blog an enjoyable and satisfying effort.

Mike