I can trace my interest in freight cars back to childhood. When the local would spot a boxcar at the grain elevator, I’d make the pilgrimage up Water Street to check it out.

My curiosity and interest back then was simpler and more innocent. The subtleties of builder dates, car classes and differences in door types, or brake wheels were lost on me. My young eyes and mind were drawn to issues of what it this , what does that do or what does the inside look like?

Do I wish I could re-examine the past firsthand with more experienced eyes? Of course I do, who among us wouldn’t love that opportunity? Since that isn’t possible, I have to settle for the next best thing: primary source material like general arrangement drawings, blueprints when I can get them, and vintage photos. As many of you know, scratchbuilding is part archeological dig, part detective case and part scavenger hunt.

Haste Truly Does Make Waste

The truth behind Benjamin Franklin’s proverb hit home with a vengeance recently as I understood with brutal clarity how my impulsive approach to modeling creates a lot of wasted time and material.

I tend to jump in to the construction with both feet. I typically do a bare minimum of planning to convince myself that I know what I’m doing. Truthfully, I hardly ever know what I’m doing. Invariably I hit a snag quickly and have to correct some obvious and often, easily avoided error. Worse, I discover a better method of doing something well after the fact. The temptation to start over is often enormous leading to more lost time and material. These situations and many others could all be dealt with simply and early on with practice pieces to test my assumptions and more time spent working out the process.

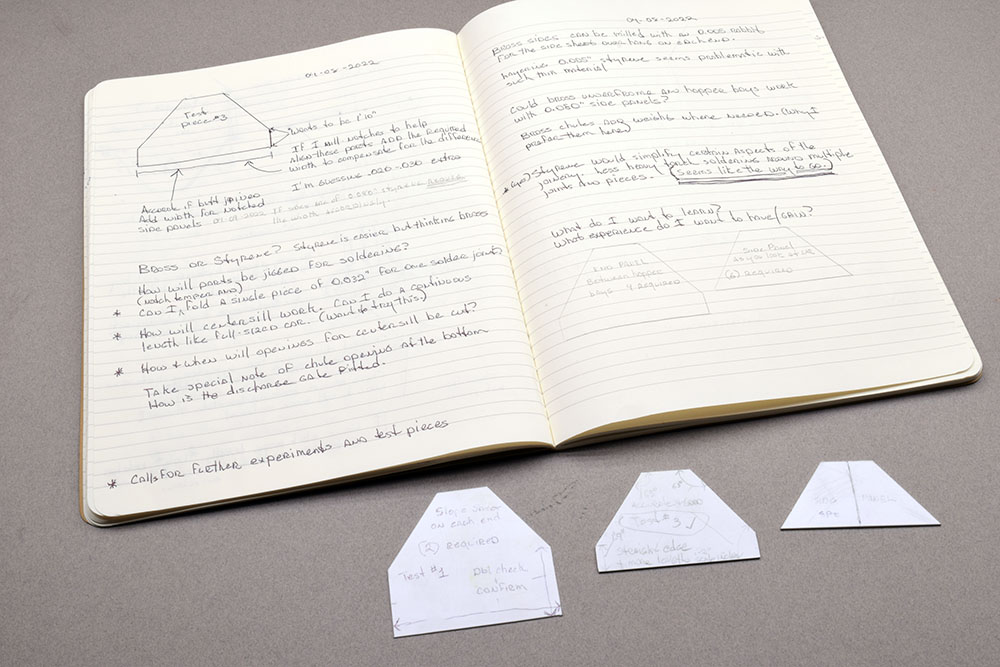

Scratchbuilding isn’t just a means to an end for me. With each project I think about what kind of experience do I want to have? What new skill do I want to learn, what material or technique do I want to explore? What status quo boundary do I want to push against? (All of them naturally.) Sketching and note making in the earliest stages are ways of exploring all these options in a low risk manner. On paper, every option is open for discussion. Material choices are free to make and consider. Problems around technique and future assembly are looked at and potential solutions are thought out.

Over the course of several relaxing and enjoyable hours I filled many pages with drawings, critical dimensions to remember and the specifics that surround different construction materials and choices. Drawing is a form of learning to see and in this case, it’s also a way of pre-building the model while exploring the best ways to do it. I understand that time spent here means a better crafted, more satisfying result at the bench. To that end, I’ve reconsidered a few early choices for the model that I hope will simplify the assembly without compromising the overall quality I want. My next steps are to test the construction methods I’ve planned to see how they work in reality. These include material choices, fabrication procedures, joinery and the like. These experiments will also help in the design of jigs and tool setups. This is an enjoyable process in its own right, so there’s no need to rush through things.

Finally, I want to lower reader expectations from the outset. I understand how I move through projects like this. They start full of enthusiasm, then hit a rough patch. I lose interest only to regain it. Things stall again, then make a little more progress and this soap opera repeats, often for years, until the model is completed or abandoned.

A covered hopper isn’t the easiest of models to build or start with. There’s a lot of geometry and planes that come together in challenging ways. It is precisely that complexity that I’m drawn to engage with. It’s my love of craft that motivates the choices in technique and materials. Such choices reflect who I am and what I love about modeling and trains. With all that said, I realize that my choices for the design and quality in a model aren’t that interesting or relevant to the majority of folks, which is understandable. Therefore I won’t provide a blow-by-blow description of this build as I’ve done in the past. I’ll touch on the project from time to time if and when something interesting happens. For now though, I’ll move on to other topics.

Regards,

Mike

Understanding What’s Important

Let’s be clear, one person’s choice won’t be everyone’s choice. Going back to 2019 I wrote this post to share why ready-to-run equipment in this scale doesn’t cut it for me. It’s a matter of being clear about what you want and enjoy in the craft.

Drawing: Thinking With A Pencil

Learn the power of sketching to explore options and problems before they become huge.

When Answers Create More Questions

It’s easy to mix details between subclasses of a car. Learning to spot small, seemingly insignificant differences makes for more accurate modeling.

I’ll Check My Notes

While everyone is unique in their approach to scratch building, I’ve found a good set of notes to be invaluable. Maybe you will too.

Resources for Information.

James Kinkaid photo archive of The Pullman Library

This has become one of my favorite places to spend time online.

Books

Vols. 11-12 of The Missing Conversation

This two volume set covers one approach to scratch building that focuses on your mindset as a modeler in addition to the how-to.

0 Comments