My thinking toward layout design has fundamentally changed. I’ve moved on from the massive lumber and plywood framework that is custom fit to a specific space. While this form offers the advantage of efficiently using space via a bespoke design, those very qualities are also its fatal flaw.

I prefer a simpler cameo format that focuses on a single thoughtfully composed scene rather than multi-town long distance running. A cameo is ideal for the type of modeling I want to do and I find beauty in the way everything is considered together as an integrated whole. The cameo is an especially good fit for quarter-inch scale, as the models are presented in a delightful manner.

As much as I like this style however, there are a few downsides. The modules can become bulky. This is both a design and construction issue. While the thin plywood I used doesn’t create a lot of weight, as more wood gets added in the form of blocking or trim, the module becomes heavier and more cumbersome to move by myself. Mill Road is manageable and the eight-foot length isn’t that great a factor, though it is the maximum size I would consider.

Is It Useful?

I’m looking for a lightweight, self-contained systems approach that includes the track, scenery and any wiring or other hardware such as switch motors. My goal is a form that I can move easily if needed, and adapt to different spaces with a minimum of down time and disruption.

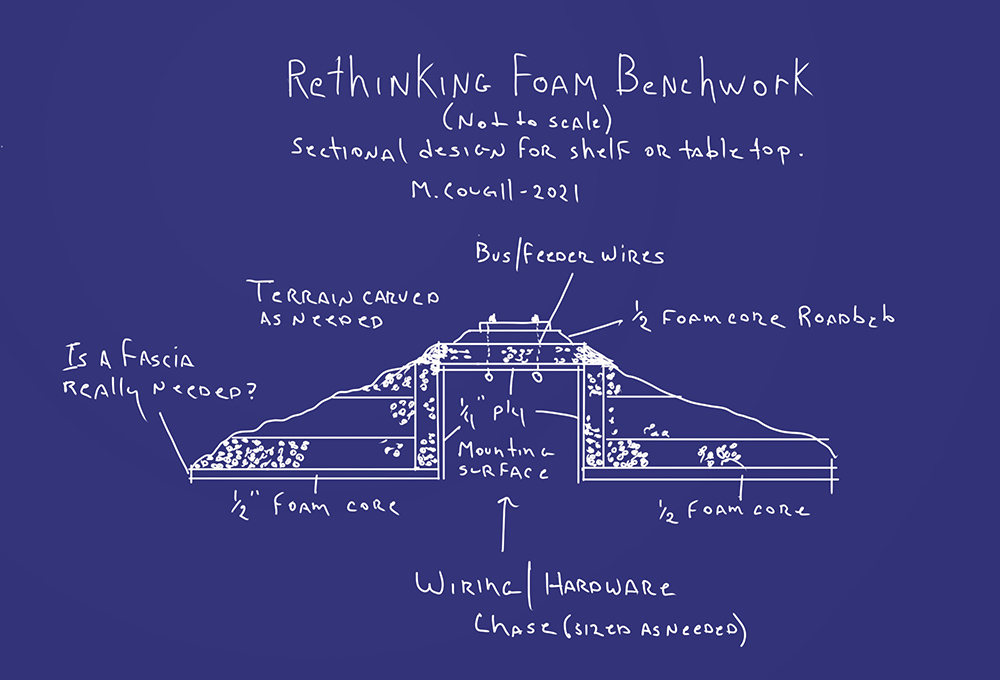

As an alternative to wood, using foam sheets, as a layout support isn’t new by any means. However, people default to treating the material as a monolithic slab that puts everything on the same level. Traditional practice is to add layers above or below and carve the terrain profiles accordingly. I’ve done this many times but now I question running multiple full width sheets below the track, as this increases the amount of material and cost, and creates a very thick surface to get feeder wires through. Speaking of wiring, how do you run and secure it? On Mill Road I used a tall front fascia to create a space for wiring and other hardware. This is one solution but what if you don’t want a deep fascia or any fascia at all?

Using solid slabs of foam across the entire width adds to the cost and amount of material plus, where does the wiring go? The idea of an inverted U shaped channel for bus wires and other hardwire integrates these items into the design of module itself while reducing the overall thickness of the roadbed. Strips of quarter-inch plywood on the sides add structural strength and pads attached to the bottom of the top piece provide a mounting surface for whatever goes in there.

I made this mockup to test different ideas and materials (photos above). I created a wiring chase down the middle and lined it with strips of thin plywood both for structural strength and as a means to protect the foam and secure bus wires or whatever. This chase can be sized as needed in both width and depth. On either side of the chase, I layered the foam as usual to create a fill for the track and right of way. Using narrower width strips reduces the amount of material, yet there is plenty for the terrain profiles.

Time To Go On A Diet

What really added excess weight to Mill Road was the fiberboard sub-roadbed from the section of old layout. This fiberboard is the usual half-inch thick material, similar to Homasote but less dense. I keep using this for hand laid track in the belief that it’s more durable and stable however, there’s no getting around the fact it’s the heaviest material in the entire construction and I’d like to find an alternative.

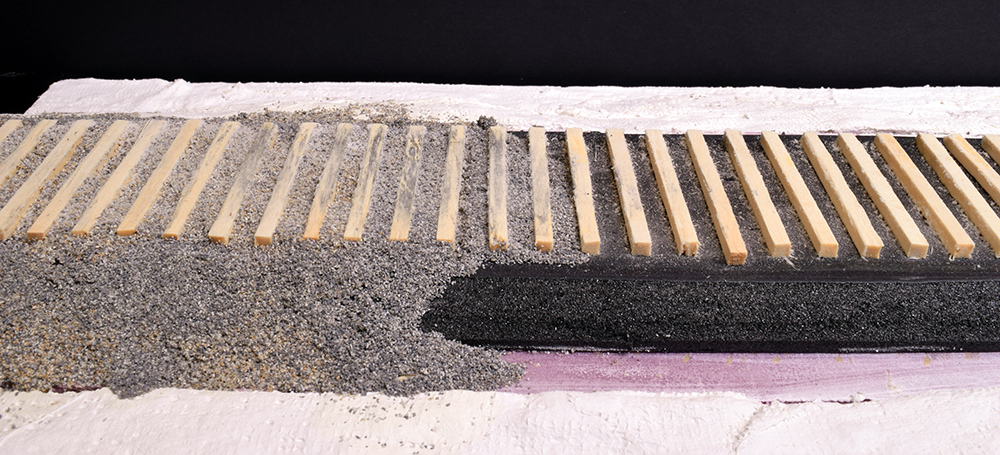

Shawn Branstetter builds wonderful handlaid track using GatorBoard (a high quality type of foam core) for his roadbed. (Link below) Inspired by his work I looked for this product locally and of course, there wasn’t any to be found. As an experiment I soaked two pieces of foam core board in water for twenty minutes and then let them air dry overnight. I wanted to see the impact on the paper facing from a prolonged wet and dry cycle, such as bonding ballast with diluted glue. Would the paper turn to mush or come unglued; is ordinary foam core material even a viable choice in the first place?

The next morning the test pieces looked and felt okay, although the paper of the white board seemed to suffer more. It’s a coated paper of some kind and the prolonged water bath must have diluted that coating to a degree. At only 3/16 of an inch thick, this board isn’t a good choice for roadbed. The ½” thick black foam board however suffered no impact that I could see. I believe whatever is used for the black coloring might be more water resistant and the extra thickness of the core is more durable.

Encouraged by this I glued up a strip of ties to test the durability of the material for spiking and normal track laying. Happily, the results were acceptable. The ties are well bonded and the thicker foam in the core doesn’t crush under the pressure of driving spikes by hand. The acid test is bonding the ballast with the usual bath of diluted white glue and water. After letting the mess dry overnight, the ties and paper facing are still secure. I’m satisfied with these outcomes of the test.

I wanted to test the duribility of the paper facing of this foam core board. Would it hold up to the typical process for hand laid track? Happily it does. The ties are well bonded and the soaking from the diluted white glue and ballast had no negative impact I could see. There may be questions about how it handles long term use but, it looks like a promising alternative to heavier fiberboard materials.

As you see in the photos, I designed this module to fit my existing support frame or even a counter top. For those with severe space constraints, such flexibility makes a layout possible.

Wrapping Up

I designed this test section to rest on my existing support frame or a tabletop. Such flexibility enables a layout to fit a wider range of rooms and circumstances.

I want a lightweight, low impact layout that fits well in a space whether it’s set up full time or temporarily. Whatever forms the construction and materials take, I firmly believe it’s possible to beautifully integrate a layout within a room without rendering the space unusable for other purposes. I’m also discovering that I need far less layout to be satisfied, both today and in the future.

I hasten to add that I’m looking at a very specific style of layout. I’ve only started to experiment with these ideas and don’t know if such materials are practical for a larger design. For a small layout though, they seem feasible and the knowledge I’ve gained is worth the time and material costs. If we don’t follow our curiosity, how else are we to learn?

Regards,

Mike

Links:

Building The Sierra Pacific Part Four

I really like your thinking here, Mike. This saves a lot of materials and weight. It’s a “modern” approach using materials that have been around 40+ years. I’m going to have to build a test module myself. There’s one change that I think would make a big difference in weight: instead of constructing this as a U channel with flat plates of 1/2″ foam core on either side below, I think you’ll gain a ton of strength by using a solid slab of foam core across the bottom that has slots cut out beneath the U channel.

These slots would leave intermittent cross-bars of uncut foam core. These serve two purposes: 1) prevent any potential stress at the corner joints in the U channel, and 2) support the wires running in the channel. The downside is that now wire has to be pulled through the channel instead of simply tucked up into it, but there’s going to be plenty of access so that shouldn’t be a problem.

The added rigidity gained with a single bottom sheet, I believe, could allow the system to dispense with the plywood entirely (depending on the span). I’ll be testing this option as well.

As akways Mike, thanks for sharing your thoughts! I always look forward to your new posts.

Hi Chris,

That’s a brilliant suggestion for adding strength and integrity to the design. I like it and will incorporate it into future versions. I will say that at 14 inches wide by 24 inches long, my test piece is stronger than it looks in the photos. The way the foam pieces are oriented provides a rigid structure that weighs next to nothing. The plywood strips really aren’t needed for strength but do provide a place to screw into for mounting a tortoise switch motor and the bus wires. What I shared is only the first iteration of a developing idea, and there’s plenty of room for improvement. I’m still thinking about the backdrop and lighting needs as I like how they fit into the design of Mill Road. Please let us know how your own experiment turns out Chris.

Mike

Hi Mike,

I’m pondering decking choices as well. I am experimenting with 3/8” cork faced foam sheet. It’s basically foamboard with a cork face on one side. I started a turnout on the material 5 years ago. I haven’t really tested it against water so I’m still a little afraid it will warp.

I have some gator board, but that’s an expensive road I’m not sure I want to go down.

Hi Greg,

I’m sure there’s lots of options beyond fiberboard and homasote. I plan to experiment some more with the black foam core material.

Mike

Mike,

I’ve followed your thoughtful journey with the hobby. Thank you for sharing your ideas and opinions!

Regarding lightweight construction, have you looked at the “waffle frame” construction used by the Sipping & Switching Society of North Carolina? I think that the goals you’re looking for might be achievable by adapting their torque tube build techniques to your needs. It is the same concept used in hollow core doors without the standard widths.

Thanks for your insight on the art of the hobby!

I’ve built several photo bases over the last 20 or 30 years using scraps of ordinary foam core left over from display jobs. It works fine, although there are one or two things you need to work around. The board can go banana shaped really well if you build up laminations using PVA glue – your box structure is a good way to avoid this. The board is also very easily damaged, which can quickly lead to tatty corners if they aren’t reinforced or otherwise protected. Joining modules reliably is also a problem if you want to build a traditional working model railroad. Not a problem for me as I’m only interested in dioramas, but an issue for others (the Australian approach using foam in an aluminium frame works well here).

Hi Tim,

Thanks for the kind words and sharing the suggestion. I looked at the system via the thread on the MRH forum. I’m certain it has the qualities you mentioned and fills the group’s need for a lightweight traveling layout. My thoughts about it are twofold: As shown in the thread, it produces a flat tabletop surface that doesn’t account for below the track terrain features, though I’ve no doubt you guys could or have modified the design to include them if desired. My second thought is related in that the design doesn’t integrate scenery profiles into the system. If you look at the mockup I made, The structure and scenery profile are one and the same. Again, I want to emphasize that these are simply my own criteria for a lightweight home layout. There are many options to pick from depending on what result you want.

Thanks again for reading. I do appreciate knowing people enjoy the blog and get value from it.

Mike

Hi Kevin,

I agree that foam core isn’t a durable material for finished surfaces like a fascia. I would still prefer a thin piece of plywood for those applications. I can confirm your experience with the curling from PVA. I hadn’t secured the test strip when I glued the ties down and it curled nicely when I removed the weights. It flattened nicely when I glued it to the module. If I go with these materials in the future, I’ll consider a foam safe caulking type of adhesive. Thanks for commenting.

Mike

Refreshing thinking, as always.

This conversation is also one about accessibility. We no longer live in a time where we all have workshops, the heavy tools, and or even the interest in screwing together miles of L girders. As life has expanded to include people who don’t want to do woodworking or wield power tools our hobby can evaluate its methods to see which ones can be teased out more creatively. Imagine insisting the artist invest in woodworking tools to cut and form the stretchers for their canvas or the same to create simple frames just so they can paint? Alternatives here are opportunities are an invitation for diversity – what can we use in our apartment and carry home on your bike or on the bus.

There’s no need to frame layouts like we do. We often are encouraging our thinking to look beyond our hobby and to others for finishing techniques and in this instance I’m wondering if there’s something we can be learning from the model airplane builders. Those large. 1/4 scale, flying radio controlled airplanes do so on wings that are complex forms built up from lightweight materials that work together to create a shape that moves through air to produce the desired flight while also is strong enough to hold the airplane together as it performs those flying manouvres. I can’t help but wonder if we looked at benchwork like ‘they’ look at wings if there might be a lesson learned?

I really like the idea of separating the structural frame from the scenic framing elements of the layout. The structural frame could indeed be a countertop, bookcase, or like box. It really doesn’t matter what it is so long as it holds our layout up at the right height and does so with enough stability that we can rely on it through the duration of a typical operating session. It’s shape is mostly irrelevant – the median width of the scene it supports (probably?) and high enough to elevate the scene to where we think it needs to be. I’m using Ikea Ivar series shelving under my Victoria project. Not just their legs but the shelving panels too. The system clips together quickly and this moves me right past framing and into finishing and that’s my hobby today and probably tomorrow too.

Having removed the structural form from the role of benchwork we’re left with a scope defined by what’s left of its role: mostly a place to tie the surface elements of the finished model railway. In this way it doesn’t require much structure at all and most of the decisions can be second to the aesthetic decisions from form. I wonder if we could start from the track plan; then design the roadbed; then move to creating a lightweight structure just rigid enough to keep the roadbed from deforming? From here, the scenery could hang from the sides like the wings of our aircraft? I used slabs of rigid foam because I could hack away at their shape quickly with a cheap utility knife. It’s far from a perfect world because the design I’m using demands wiring and everything else be surface mounted (hiding a turnout mechanism or routing wire is just better if it goes under the ground not laying on top of it)

I believe that traditional benchwork is antithetical to the fluid form of the scene in our mind’s vision. Slabs of foam or plywood or even the typical stick framed benchwork all undermine the fluid nature of the natural landscape we’ll eventually define our model railways with. Traditional thinking quickly establishes a perimeter that is reinforced by the mass of the structural weight from the benchwork and that consistently dominates everything within the scene – ironic because “what’s in the scene” is what we built the model railroad for in the first place. If the layout’s form could be released by this thinking, it too could be just as fluid; it’s perimeter less defined. Imagine the profound effect this could have on obviating so many typical model railway design issues like track running parallel to the front edge, shadows on the backdrop, or that feeling of barrier created because we are always outside the model because creative a more embracing footprint for our benchwork is just too difficult in plywood? All those compromises just evaporate and my mind is blown by the possibilities exposed by this wake.

You asked about ‘no fascia at all’ and I wonder what that would look like? It asks a question of the artistic role of fascia. I’ve always thought of it like the white space around the perimeter of a photograph used to create a transition as we focus on the photograph but that’s not something we do in a painting. Interrogating the role of fascia–why we include it and what we think we’re achieving with it–might be a fascinating conversation to have sometime.

Thanks again. I love reading your work.

Chris

Hi Chris,

I take woodworking for granted since I have the tools and a space to set them up when needed. Your observation that fewer people have such access or any desire for it is one I hadn’t considered. But I suspect it’s a real barrier for many who would otherwise consider the craft. You’re right we do overbuild the bench work for reasons that have more to do with tradition than what makes sense for your situation. The analogy of model aircraft construction is an instructive one.

My cameo modules have more than enough strength and rigidity, yet are far lighter than traditional practice. These days, I’m looking to eliminate as much wood as feasible from any design and definitely looking at new materials. I agree about separating the modeling from the support structure. Like your current effort, my cameos could live on a long countertop as easily as the rail system I built. We both know that flexibility is the beauty of the system.

You make interesting points about free form edges that allow for different viewpoints for a scene. Such thinking brings a refreshing vibe to layout design conversation and any perceived limitations come from our own lack of imagination. There are endless possibilities here. I also agree about the white space effect of the fascia. You’ve broken that ground already with some of your previous ideas, perhaps we should carry that conversation forward? I’d love to see what you and James would come up with. As always, thanks for commenting Chris.

Mike