What I want from the craft has grown simpler in recent years. Dismantling the old layout was not fun and I don’t want to repeat the experience. Quarter-inch scale showed me the realism that’s possible. The old layout helped me understand what I want, and for the new project, it’s time to bring the two together in a more thoughtful way.

Over Yonder Really Isn’t

Regardless of the modeling scale, the bane of every layout design is representing the vast distance a railroad covers. In our attempts to reduce the real world to the confines of a basement or spare room, we employ a variety of tricks. Some are useful, while others border on the silly.

Representing distance in quarter-inch scale quickly becomes problematic when a single freight car is 10-12 inches in length or longer. A couple dozen such cars eat up many feet of wall space before the train even moves an inch.

Design Looks At The Whole Picture

We tend to limit design thinking to the trackplan or operating scenarios. In my view, design thinking applies to the entire layout and presentation.

I want to feel like I’m in the modeled scene rather than hovering like a drone up in the sky. This eye in the sky viewpoint greatly skews our perception toward large sweeps of the landscape and many people likely think it’s the only option. Yet, in real life, we seldom see the railroad from above. We might get a glimpse from a bridge or tall building but those are more the exception than the rule. For the most part, we’re at ground level, next to the tracks, where our field of vision is smaller.

Warts and all, this is the immersive perspective I want to see and experience on a layout.

I watch L84 from the crossing at 12th Street, because it’s where all the action takes place. The locomotive will pull a string of cars and begin sorting them into spot order. With a long cut of sixty-foot covered hoppers the engine could be several blocks away from where I’m standing. If I moved down to the other end of the yard where the power is, all I would see is the engine repeatedly shoving forward and pulling back a few car lengths. Not that interesting, since the real action is at the other end.

Even a modest operation like this requires more space than I want to devote to a layout. I’m so familiar with this area that the amount of compression involved to fit it all in would ruin the sense of place for me. Furthermore, it would be a closed world, with nothing left for the imagination because the train couldn’t leave the scene, which in my view, is critical. That’s what I wound up with in the final stages of the old layout and it proved unsatisfying.

I’m using this operation as an example only. If excessive compression is the source of so much frustration in layout design, then I prefer to selectively eliminate elements instead of squeezing them down into cartoon caricatures.

Design Solves Problems

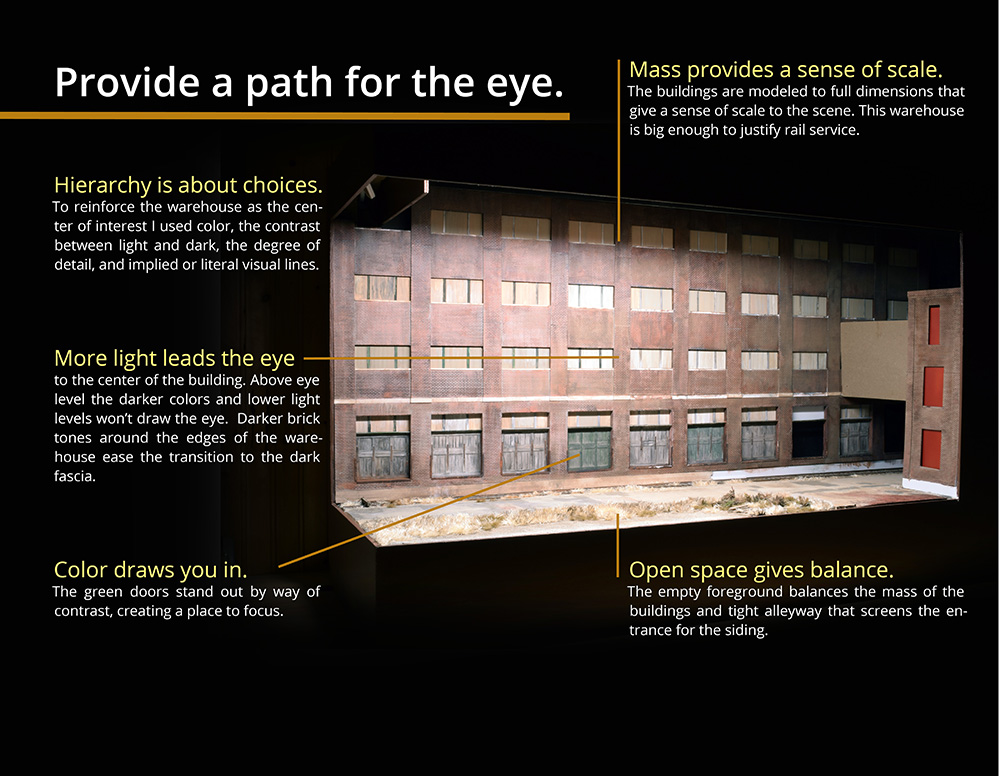

The 13th and North E cameo convinced me of the power a simple composition has. Even though the warehouse is nothing more than a flat, the full-scale width and height give it a commanding presence that’s hard to ignore. It’s that sense of scale between the trains and their surroundings that is sorely missing in modeling.

What the cameo format provides is framing and focus. Like site planning for a building, there are boundaries and conditions that influence what can and can’t be done. The finite real estate forces one to focus on the essentials and eliminate everything else.

Q: Okay fine, but it seems like a waste to separate each cameo with plain track. Operationally, you need the track anyway so why not add scenery?

A: For the same reason most people don’t add scenery to their staging yards. Plain track and surroundings don’t draw attention. Like off-scene staging they provide a place for the train (and our imagination) to go. And, as I said, if we can see all of the scene then we think that’s all there is to it.

Q: Why not frame individual vignettes, but connect them directly to have more scenes in a given space?

A: That could work, however, the abrupt transitions between different scenes create a hodge-podge look. If a siding runs across two separate scenes, how would you explain the string of tank cars from the refinery of one scene that overlap in front of the warehouse on the other? The plain track in between serves as buffers against such things. It’s the empty space in between that provides the contrast and balance. As a train enters or leaves a scene it disappears and we don’t know how far it is to the next encounter. Think of the impact of a train going through a tunnel. Even if it’s a short one, there is that time and space, however brief, where the train vanishes and we anticipate its return.

Q: If tearing out a layout is a pain, why not build it in module form that’s easy to move?

A: I’m not a fan of modular construction. Running a scene across two or more modules adds unnecessary complication in the form of more rail joints and wiring connections. There are gaps in the scenery and backdrop that have to be disguised along with alignment issues and so on. Unless you plan to move it regularly, what do you actually gain with such construction?

Also if you move, what happens if the new space is much smaller and there isn’t room for the set of modules as designed? Opinions will vary widely of course, but I prefer each scene to be self-contained within a single cameo. I believe there is more flexibility that way. Elegant design solutions are there for the taking, if one looks hard enough.

Conclusion

Let me categorically state that this isn’t for every taste and I’m not suggesting it should be. These ideas are simply my thinking and preferences at this stage of the journey.

Mike

0 Comments