I’m aware that with limited time for a hobby, coupled to a desire for tangible progress on a multitude of layout projects, doing something simply for practice to improve your skills is uncommon.

It’s important to understand that your interests in the craft may change with time. I’ve reached the stage where my main focus is on model building rather than another layout. Like others however, I also often ignore practice pieces even though I know the value they bring to my modeling. Since I’m a rank amateur in working with brass and have so much to learn, I feel a greater desire to practice some basic skills.

Layout

I don’t have to tell you how important and fundamental an accurate layout is. It’s where craft begins the journey into the real world. I quickly discovered that metal demands a focused approach, as brass is unforgiving of sloppy working habits. Unlike plastic you can’t flood a joint with liquid cement and mush it together to make a gap disappear.

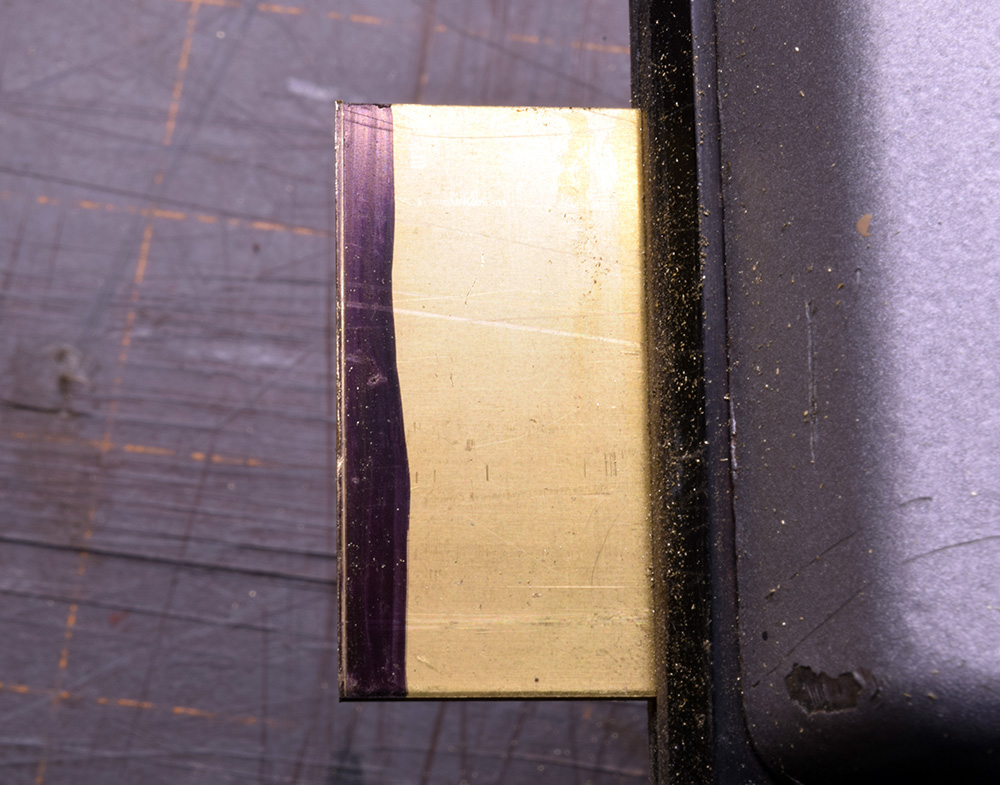

I use a caliper or pair of dividers to take measurements off my scale rule and then transfer them to the material. I have one scale rule that I only use for dimensions to ensure consistent accuracy. I set the calipers to the spacing I want and run one blade along the factory edge of the material and scribe my line with the other blade. To enhance visibility of these layout lines I coat the material with a felt tip marker before scribing. I know there are specific marking fluids for this purpose but the marker is durable enough to withstand handling and it cleans up easily with denatured alcohol.

A coating of permanent marker enhances the visibility of this scribed line, making it easier to file down to it.

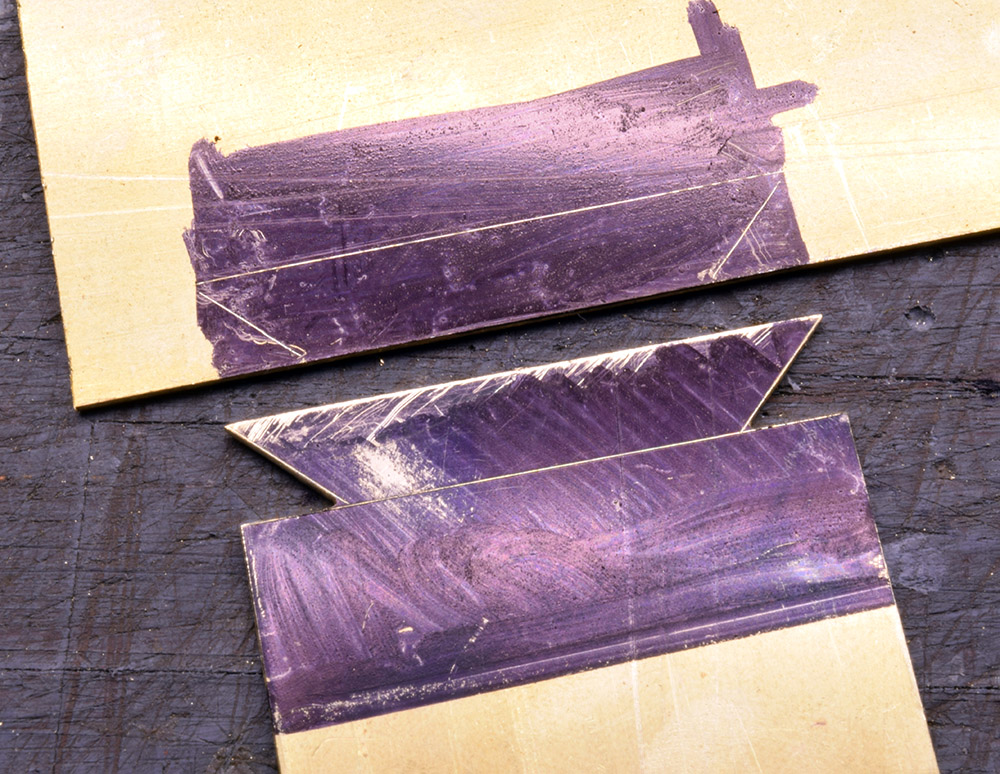

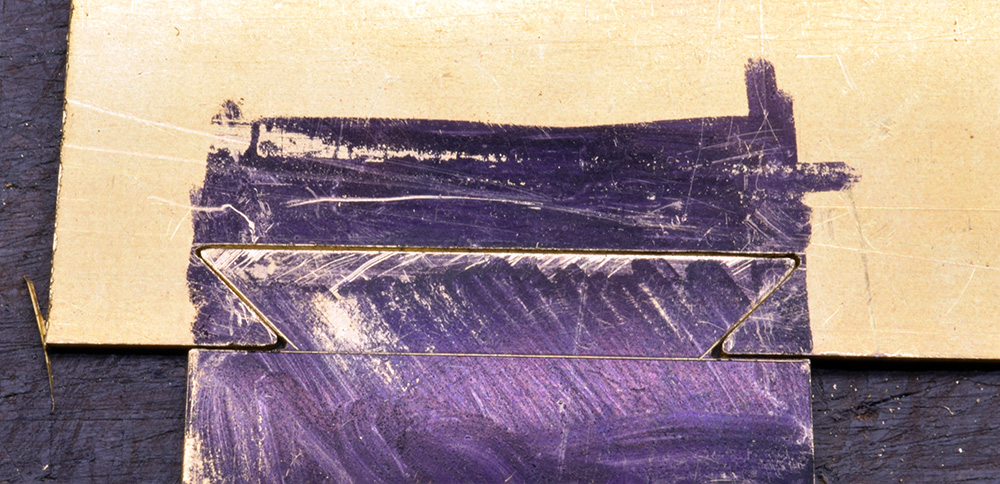

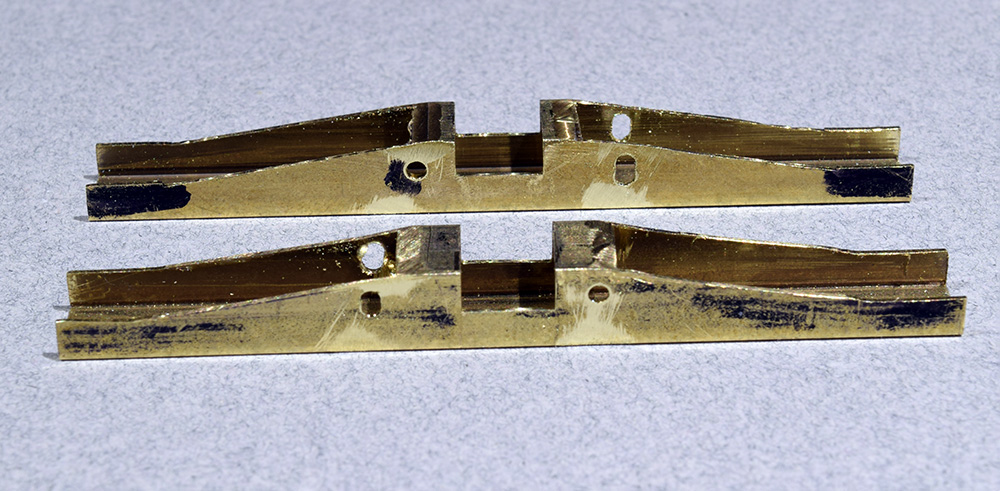

For this exercise I traced the layout of the dovetail pin from the lower piece and went to work removing the waste material.

Unless it’s clearly off, I trust the factory edge of the sheet brass. Depending on the thickness of the material, if I need to true something up, I use either a mini table saw with an abrasive cutoff blade or my mill. With proper setup, the mill provides greater accuracy for thicker sheets, while the table saw is better for thin stock. For the typical 0.005-inch sheets I use, a modeling knife and light cleanup with a file often works just as well and is safer.

Before scribing I double and triple check for square corners and parallel edges. As with the scale rule, I purchased a new square to use only for checking parts as I’ve found enough differences in my older tools from wear and other abuse to warrant this precaution. Depending on what you want from a build, these steps all make a difference in the accuracy of the layout. All these steps are a matter of choice, as I’m after a precision fit for each part. I also want to develop good working habits so I take the time to get things right from the start.

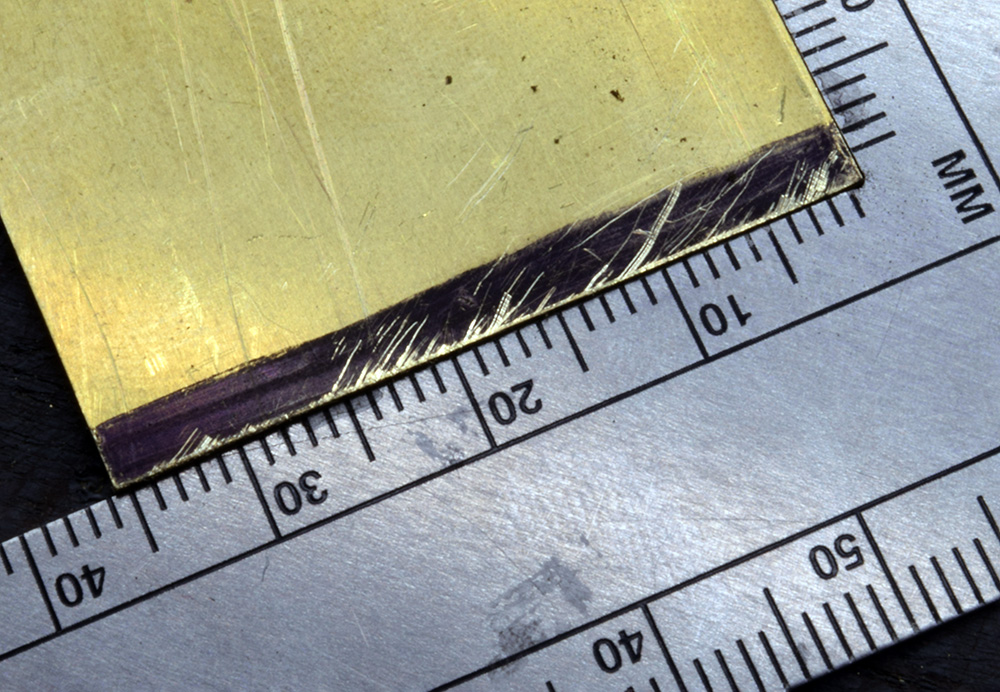

Square edges are key to a satisfying fit. I’m learning to take my time and pay attention to the progress of the work. There’s no going back once material is removed.

Fitting

This is where I need the practice and the reason I do these pieces. My impatience and poor habits are in full flower at this point. As mentioned, brass is unforgiving. If the fit is off, there’s more work to be done. If I remove too much material, I can’t glue on a filler piece to compensate.

I’m learning how to slowly bring an edge down to my layout lines. Unlike woodworking or styrene, I don’t try to cut to the line. Instead I leave a bit of extra material and refine the edge with files until it conforms to the line. It’s a lot of trial and error and testing the fit until it’s where I want it. My tendency to rush and be aggressive with the files is my worst enemy. It’s easy to remove too much material and go past a line. I have to learn how to let the work dictate the pace. As you’ll read in the photo captions rounding an edge and having it out of square creates visual gaps in a joint even if the edges contact below the surface. These minor gaps are quite distracting, as I want a visually tight joint.

It’s a sloppy fit for certain. I made the sharp corners of the dovetail pin with the table saw, and didn’t realize I don’t have a file capable of making such tight inside corners, so I modified the design on the fly, resulting in this poor fit.

Gaps like these come from a number of factors like rounded edges. On thin material it’s easy to tilt the file this way or that and produce an edge that’s out of square to the face of the sheet. The image below is slightly better but still has a long way to go.

We treat mistakes as something to avoid at all costs, yet this is the place to embrace them and learn what needs to be learned. These simple pieces taught me more than a library’s worth of books on theory and instruction.

Shaping parts to a specific dimension is a fundamental skill. These practice pieces help train my eyes and create a space to develop good tool techniques. I’m gradually getting there but it’s a constant struggle for now just learning what the mistakes I’m making are. This is what I speak of when I suggest a craft shapes us as much as we shape our craft. The degree of precision I desire will only come from practice and unlearning bad working habits that are deeply engrained. I’m comfortable with styrene and it’s easy to believe I can immediately have that same degree of familiarity with brass. That’s a self-inflicted lie. Time and the work itself are my teachers here.

Skill Takes Time And Results Will Vary At First

Knowing something and doing it are two different things. If I don’t sit down at the bench and take tools in hand, I’m never going to develop as a modeler. Being deliberate in practice is worth the time and effort.

I’m looking for long-term consistency in my growth as a modeler. There’s a never-ending road ahead, yet I enjoy being in unfamiliar country again. I believe we grow too complacent in this craft by simply repeating the same things over and over. It isn’t everyone’s cup of tea but the answer to boredom for me is found at the bench facing new challenges that stretch me out of my comfort zone.

Of course, the purpose of practice exercises is to improve the quality of finished work. The mill simplified the work on these bolsters and I’m happy to have one in the shop. That said, I believe we can impoverish ourselves by an over reliance on technology. I value and enjoy the direct impact that working with materials. Even with advanced machine tools, learning good hand skills always pay dividends. This awareness helps me focus on aspects of the craft that offer the greatest return for my efforts. Thanks for reading and I hope you found something useful to apply to your own work.

The Mandatory Disclaimer:

Metal work and the related machinery can be dangerous. Use proper eye and hearing protection around machinery and if a procedure feels stupid, it probably is stupid, so don’t do it. Use common sense and safely enjoy your modeling for a long time.

Next time we’ll consider how good quality tools enhance the work.

Regards,

Mike

As a jeweller let me just say that best practice would be to split the line rather than filing ‘to’ the line. With practice you can even use a jeweller’s saw to split the line, or shave the line and finish with a file. Also don’t underestimate the importance of workholding to accurate work. You could grab a few jewellery books from the library to see how it might be done — it’s an ancient craft that embodies a great deal of wisdom and experience in fabricating small items.

Hi Andrew,

Thanks for commenting and bringing the perspective from another craft. I’ve looked at books on jewelry making to learn fabrication and other metalworking techniques. There is much we could learn from a craft such as yours and I will take your advice.

Regards,

Mike

As a spotty yoof I found an outstanding guide in Herbert Maryon’s ‘Metalwork & Enamelling’ – originally published in 1912, updated and revised until 1971 and reprinted by Dover Publications.

Sounds interesting Kevin. I have a couple of old textbooks my dad used in his work. They’re oriented to industrial processes but still interesting.

Mike