The blog discussions get far more interesting when I stay out of them. I appreciate and have enjoyed reading the comments on the last post. Thank you guys for taking time to offer such thoughtful commentary. Inspired and curious about the details in my photo, Chris, Dave and Matt touched on aspects of modeling that I hadn’t thought of: how to capture the essence of the past. I thought I would provide background context from my experience of that time and place.

Getting Oriented

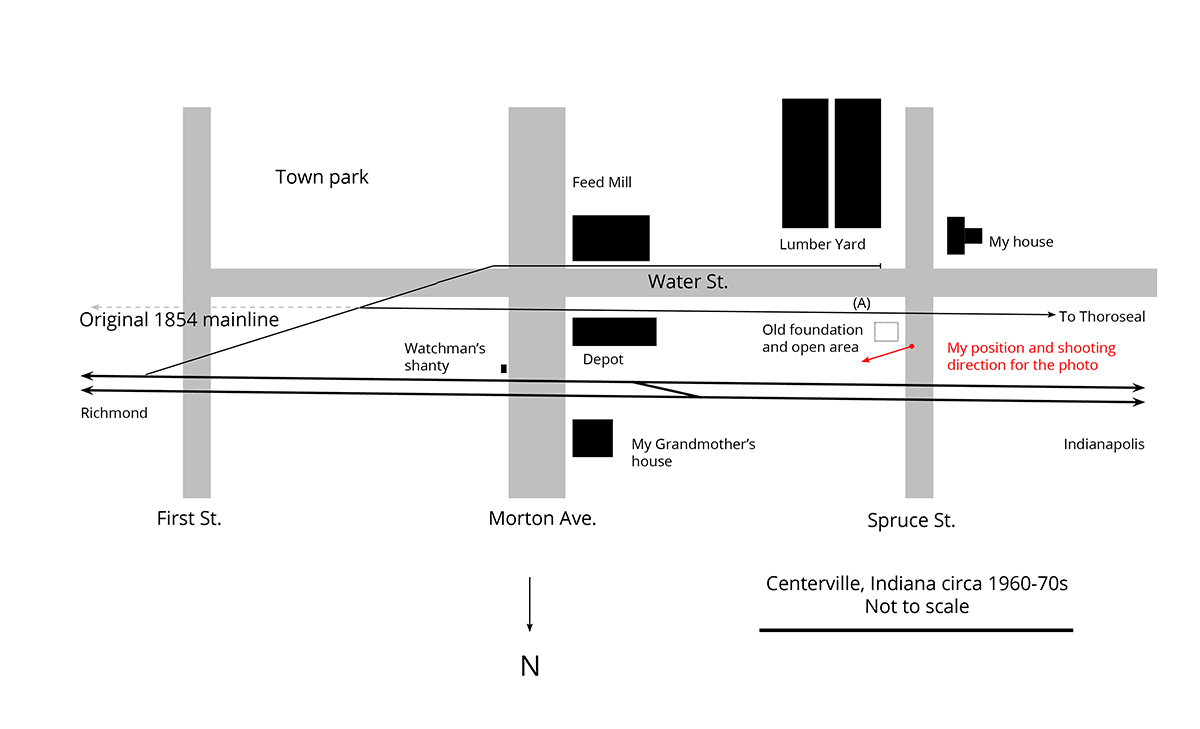

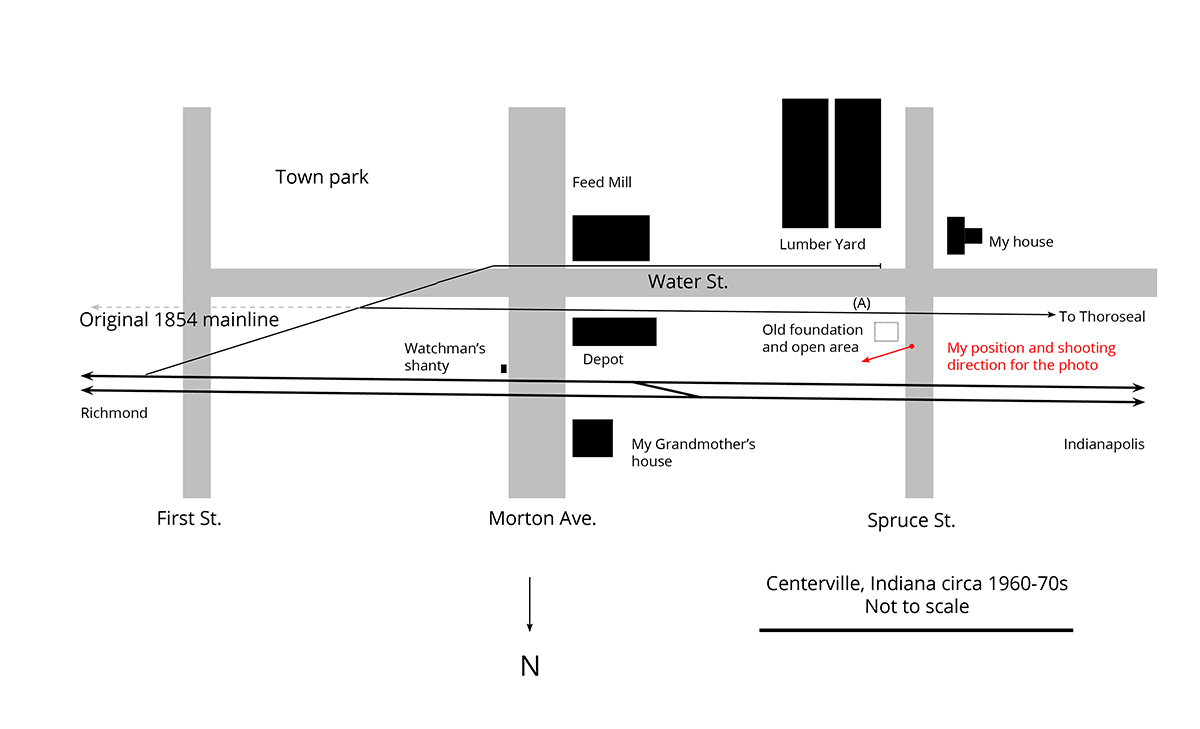

This illustration should give the lay of the land and help you see the relationships between the railroad, my childhood home and the nearby streets that I’ve described so often. The red dot with the arrow shows where I stood and the direction I faced while shooting the image in question.

This was the PRR’s Lines West, running from Pittsburgh to Saint Louis. This specific portion was part of the Columbus Division from Columbus Ohio to Indianapolis, Indiana. I don’t recall the exact date of the photo but I know it’s after the 1968 merger between Pennsy and the New York Central. The caboose on the tail end is an NYC way car, which never would have run here before the merger. Notice the differences between the two cars. The NYC car has only a short bay window extension while the mystery caboose has a full height window bay.

From what I can tell from the blurry image, the mystery caboose looks like a Southern Pacific car (look at the large lettering in the upper corner and the difference in the black and white halftone shades, that indicate different colors). If this is the case, I have no idea how or why it’s on this train. As Dave suggested, there is a reason that it’s here but that reason is lost to history. It could have been part of an equipment lease, or a transfer run through. I simply don’t know. All I can say is that after the merger a lot of unusual equipment started coming through the area as part of the massive shakeup and restructuring of railroading in the late 1960s and throughout the ‘70s. That era was a watershed period that shaped the modern industry we know today.

Oh Those Conveyors

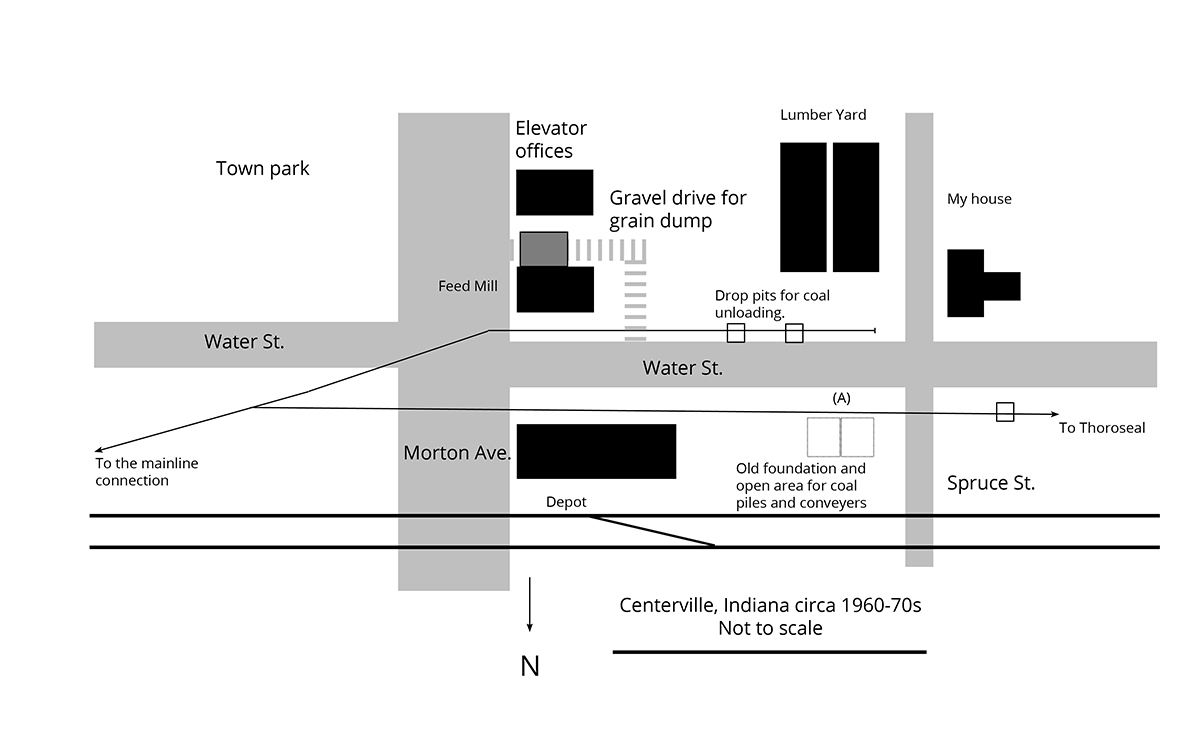

I’m surprised by the amount of interest the two material conveyors generated. The explanation for their presence is pretty straightforward. Looking at the drawing, you see an open area east of Spruce Street. The elevator once had a small retail coal yard here, mostly for people with coal fired home furnaces. Even in the mid-to-late sixties, I recall a pile or two of coal being stored just north of the siding to Thoroseal (you can see the coal pile in the photo). The local would spot a coal car on this track and a worker would unload it with the smaller conveyor seen in the rear. This was an infrequent operation as the business was minimal by this time. I suspect if one were to root around there today, you could still find some coal in the ground.

The light colored conveyor in front was used to unload covered hoppers of fertilizer or other dry bulk farm products for transport by truck. Again the local would spot a car at location (A) on the drawing above, near the corner of Spruce and Water Streets. A big open bed farm truck would pull up on Water Street next to the car and load the dry material with the conveyor. As you can imagine, unloading a 70-100-ton hopper car in this manner could take all week or longer. If Thoroseal needed switched before the car was emptied, the local would shove it back to the plant to do his work and re-spot it as the last move before leaving town. To Chris’s questions about whether these conveyors are still in use or remnants of the past, they are both. The coal business was over yet the conveyor remained for a time. Both were stored next to the siding when not in use, as a matter of pragmatism. In those days, no one would bother anything, so they were safe.

Switching Town

Centerville was the westward limit for the yard jobs from Richmond. The double track through town was actually considered a single track with continuous passing sidings formed by strategically located crossovers that allowed faster trains to get around slow ones if needed. Traffic generally kept to right hand running but could use either track with clearance from the various tower operators. Normal practice for the local was to arrive on the north (westbound) running track and stop short of the crossing at Morton Ave. But sometime he would arrive on the south main, thus eliminating the need to switch tracks via the crossover.

Assuming normal practice, the brakeman would use the call box for permission to unlock the crossover before signaling the train forward. After switching tracks and resetting the crossover, the train backed down the south track to the east of First Street, where the crew performed a flying switch maneuver to get any cars on the opposite end of the engine. The sidings dropped down from the main and the cars would move at a good clip with a brakeman riding the lead car and working the handbrake all the way to the Thoroseal plant three blocks away. As a kid, this was fascinating to watch. While I suspect a stunt like that wouldn’t be tolerated today, these guys were pros and could stop the cars wherever they wanted. Meanwhile the engine followed down the siding to recouple and then work the plant. If the situation called for it, the crew would leave a cut of cars on the main while they switched. They had an authorized window of time to occupy the running tracks and did the work in a leisurely but efficient manner. Unlike model operations, there was no sense of rushing around to get out of the way of a through movement.

The elevator track ran along the south side of Water Street. It came off the original main between Morton Ave. and First Street. Both tracks and the street were at grade and the rails and ties were buried under old ballast, cinders, weeds and dirt. This was a small local operation that closed by the late seventies or early to mid-eighties. I don’t recall the actual date.

Rail service eventually stopped in favor of trucks. Some of you may recall the national farm crisis of that time brought on by overleveraged debt. Small town elevators like this one began to close as a result of consolidation to larger grain handling operations and changing farm economics.

Rail service was basic. The elevator only loaded one car at a time from a single chute. Just west of the building was an exit drive from the grain dump that had to be kept clear for traffic (close-up drawing). Off spot cars were stored on the siding toward Spruce Street or east of Morton Ave. Traffic was light except for the harvest season.

One year there was a bumper corn harvest that warrants mention. I remember there was so much corn the elevator got permission to close Water Street east of Morton. They spread heavy plastic sheeting on the street, enclosed it with snow fencing and stored the excess grain in the open until they could process it. The railroad kept busy switching cars in and out for several weeks. I once counted 17 boxcars in town and they were stored everywhere on both tracks. It was a perfect example of how two tracks could provide a switching challenge from shuffling cars around into spot order.

Other Things of Interest

As shown on the drawing (repeated above to save you from excessive scrolling), there was a watchman’s crossing shanty near Morton Ave. It was replaced in the mid-1960s by automatic flashers and gates. The small concrete foundation near Spruce Street was likely a tool shed and stores for section gangs. The footprint was around 12×20 or something like that and consisted of two sections. My dad recalled a water tank for locomotives located nearby, so this could have been a pump house. I have no information on the building though I imagine it was of standard PRR maintenance design.

The depot next to Morton Ave was the original Indiana Central station dating from the 1800s. It was long closed and finally torn down in the mid-sixties. Made of brick construction, it was a combination freight and passenger depot with an operator’s bay on both sides. My grandmother’s house was directly across the tracks to the north from it.

My memories of the time weren’t that different from today. I lived through it so they seem perfectly normal to me, just as things do today. The times have changed of course, dramatically. We forget or don’t realize how different things are because the changes happened gradually over a period of time. It’s only in looking back that we see the bigger picture of change.

To Dave’s point about modeling the past without letting the influence of the present intrude; I would only say that it’s a hard one to ponder. We are the product of our time and experiences and it’s hard to not see everything through that lens. When I look at my old photos I have the advantage of having been there in that time and place. I admit my memories may be rosier than the reality but I at least have a reference to draw from. Looking at images of places I’ve never experienced first hand I’m in the same situation as Chris and Dave. There are so many questions to ask and answer, and little more to guide me than guess work. It’s what keeps the craft fresh and interesting.

I will say that my experience of this location and the unfettered access to the railroad profoundly shaped my interest in the craft. I saw plenty of through trains but that form of operation never captured my imagination in the same way watching the local work town did. I’ve never had any real temptation to model Centerville in any scale. I realize it would be a trap with no way out. My memories are so strong that any modeling wouldn’t live up to them. Instead I’ve learned to distill the features and operational qualities I so enjoy into Mill Road. This is as close as I will get to recreate those times from childhood. For more on this idea, see Matt’s most recent post (linked below). It’s excellent.

Guys, I hope this sheds some light for your questions.

Regards, Mike

Link: Hedley Junction

Mike,

I enjoyed your trip down memory lane. I grew up and lived in west central Ohio. While I don’t have the same memories of trains (there were none anywhere near me), I did have the opportunity to travel around that part of Indiana as a young salesperson in the late 70s. I saw the ghosts of many towns like your Centerville.

I am looking for a new project railroad and something styled after this may fit the bill. Like your young self, I am not interested in the long through freights but lean more to the slow, relaxed shuffling of cars in a small town. Maybe one of those Proto Throttles, a Geep, and some freight cars would provide the relaxed atmosphere I need.

Thanks for sharing.

Pete

Mike

We re moving in two weeks, my 26 x 13 switching layout came down today. One thing I learned is for me it is more about building stuff and presentation instead of operating sessions with multiple participants. My next layout will be much smaller. I am with Pete, your post on Centerville looks interesting, and I am a Pennsy fan. I also see my future layouts smaller with a shelf life. Tear it down every 2-3 years, do something else. I enjoy your posts, always thoughtful.

John Moenius

Thanks guys, I glad you’re able to find something of personal value in the post.

Regards,

Mike

Mike, a wonderful commentary on a fascinating fragment of railroad history. Your narrative, maps and photos illustrate the depth of fascination, modeling opportunity and operation a small scene can provide if you just stop long enough to watch and learn. Another strong argument for the satisfaction inherent in building a small but deeply meaningful prototype-based model instead of filling a basement in the mad hope of “having it all.”

Thanks for clarifying and for pulling us into the scene, a scene with which I have no prior personal experience but that I now feel somehow closer to and curious about.

Good morning

I really enjoyed reading through this post. It does a wonderful job of stitching together these individual scenes, responding to our comments on the previous post, and also connecting times when you’ve shared thoughts on these places in the past. Tracing your steps across that map makes it easy to see why you have the connection you do to this place.

I thought about why the too literal approach of prototype modelling challenges the integrity of our memory and that cost could never be worth the value of anything we make to represent it. There’s no doubt in my mind that you have this strong connection to this place and these scenes. It would seem obvious that you could use this as reason to base a model railway on this place, at this time, as a way to return to “here”. What a great way to use the hobby as language to communicate something so important to people you want to share with. It seems ironic that the process of translating a richly detailed memory into a tangible form doesn’t refine the signal but instead distorts it. While memory is dynamic the model is static so demands we make decisions on what to include and what to edit out. Editing should be a way to clarify the form of a work but in this case, where the purpose of the model is to represent the value of the memory, editing is weakening the connection by reducing the number of connection points. Maybe it does that by asking you what to include or exclude because it doesn’t fit inside the envelope of the benchwork or maybe the choice of one season instead of another costs us a connection to one memory exchanged for another of equal but different value?

Rereading my paragraph above it occurred to me that my thoughts are in reference to prototype modelling on the scale of modelling one real town or any equally focussed scene and perhaps my comments are less relevant when prototype modelling is the approach for modelling an entire railroad. That the high level view of modelling an entire railroad division isn’t represented on the individual human level where a place like your Centerville or my Charlottetown is too direct, too much an individual level, zoomed in too close.

Thanks to your notes in this post, we can see how Centerville informs Mill Road. While Mill Road isn’t a real place it is infused with such an intensity of concentrated emotional it is made real. While literally recreating Centerville in miniature might be an example of how editing unfortunately disconnects you, Mill Road is enriched by the way it acts as a medium connecting what interests you in the hobby and what informs your personal history.

Chris

Mike,

If one were model Centerville, well you would have to put in a run around since flying switching would not work in our model railroads, right. Traditional thinking. Over on the blog on MRH there is a real railroader JD Hill who posted ‘Switching a Simple Spur” based on his experience on the defunct Erie Western. He solved the problem of just moving the cars with his finger.

In a cameo layout where you only have to please yourself why not. Given your posts frequently challenge the norm I thought this was interesting.

John Moenius

Thanks for the comments guys. Chris, you’ve given me an idea for the next post.

John, why not indeed. I’m aware of Jack’s work as he reads this blog. He does wonderful work and his insights on how things work in the real world of railroading are pure gold.

Mike

It’s funny how reading this post changes my own relationship with it and matures the connection to it.

When you first introduced Mill Road I connected with the way it celebrated minimalism in design. That it uses a volume of space that is not unfamiliar to me but uses it in a way that I have never tried. I liked what I saw and really liked how it challenged me to think about the space in a way I wasn’t considering. That original set of connection points is probably mostly selfish on my part since they’re based in my identifying things I find compelling. Following your work and the evolution of this as you tease its form out has been a fascinating opportunity in how we can be involved within the creation of the model. Reading this post, this week, that initial relationship widens with this background. It helps to start to see things in the layout that maybe you see and now my limited set of initial connection points are joined by yours and the quality of the communication is made better.

If the model railroad is an article of communication this is the example that proves how we communicate through the medium of model railroading. That’s fascinating because that’s like a kind of language.

Chris

Chris, you’ve nailed one aspect of truly injecting art into modeling. Going too literal does not make an interesting scene; an artist crafts the viewer’s experience.

And Mike hit the other. Injecting the personal into a scene brings the crafted scene into perspective and connects it to the viewer. Before your narrative, the photo was all about “what’s going on here?” After it became a story to draw us in.

There have been so many articles in the mainstream press, and a book or two recently, that attempt to explain art into our modeling and I’ve found almost every one falls short. Your post is one of the closest I’ve read to nailing the topic, when linked to the models I’m seeing you make, because it is clear that your strong narrative telling tied to your color use, compositional play and level of craft underlays your core design aesthetic. Truly inspirational.